Use of complementary and alternative medicine in connection with cancer [study]

Abstract Background Research exploring the use of specific modalities of complementary and alternative medicine (here referred to as alternative medicine for shorthand) by Norwegian cancer patients is sparse. The objectives of this study were therefore to map the different alternative medicine modalities that cancer patients use and to further examine their reasons for use, communication about use, self-reported benefits and harms, and their sources of information about the different modalities. Methods In collaboration with the Norwegian Cancer Society (NCS), we conducted an online cross-sectional study among members of their user panel with current or previous cancer (n = 706). The study was conducted in September/October 2021 with a modified cancer-specific version...

Use of complementary and alternative medicine in connection with cancer [study]

Abstract

background

The research exploring the use of specific modalities of complementary and alternative medicine(For abbreviation here only referred to as alternative medicine)by Norwegian cancer patients is sparse. The objectives of this study were therefore to map the different alternative medicine modalities that cancer patients use and to further examine their reasons for use, communication about use, self-reported benefits and harms, and their sources of information about the different modalities.

Methods

In collaboration with the Norwegian Cancer Society (NCS), we conducted an online cross-sectional study among members of their user panel with current or previous cancer ( n = 706). The study was conducted in September/October 2021 using a modified cancer-specific version of the International Questionnaire to Measure Use of Complementary and Alternative Medicine (I-CAM-Q). A total of 468 members, 315 women and 153 men, agreed to participate, which corresponds to a response rate of 67.2%. The study was reported in accordance with the National Research Center in Complementary and Alternative Medicine (NAFCAM) model for reporting alternative medicine use.

Results

A large proportion of participants (79%, n = 346) had used some form of alternative medicine, with an average of 3.8 modalities each (range 1–17); 33% ( n = 143) had visited an alternative medicine provider, 52% ( n = 230) had used natural remedies, while 58% ( n = 253) had used self-help practices. Most participants used alternative medicine to improve quality of life, to cope with cancer or for relaxation/well-being (64%-94%), mostly with high levels of satisfaction and low rates of side effects. Few used alternative medicine to treat cancer or prevent its spread (16%, n = 55). The main sources of information were healthcare providers (47%), the Internet (47%), and family and friends (39%). More than half (59%) of cancer patients discussed their use of at least one alternative medicine modality with a physician.

Conclusions

The results of this survey will provide healthcare professionals with greater insight into patterns of alternative medicine use by cancer patients and enable more informed conversations with their patients. Given the high use of alternative medicine, reliable provision of information that supports patients' knowledge and health literacy in cancer care, as well as good communication, are critical. The collaboration between NCS and NAFCAM is an example of how these issues can be addressed.

background

In Norway, around 35,000 people get cancer every year, more men (54%, n = 19,223) than women (46%, n = 16,292). prostate (14%, n = 5,030), breast (10%, n = 3,424), pulmonary (10%, n = 3,331) and colon cancer (9%, n = 3,121) are the most common types of cancer in Norway. The median age at diagnosis is 70 years for men and women. Thanks to early detection and new and more targeted treatments, almost three out of four people now survive their cancer, and those who do have cancer live longer with their disease. The number of cancer survivors is increasing and at the end of 2020 there were 305,503 people living who had previously been diagnosed with cancer(link removed).

Complementary and alternative medicine (alternative medicine) refers to medicines and practices that are not part of standard care(link removed)and are predominantly offered outside the public health system(link removed). The term alternative medicine generally includes modalities offered by providers, self-help practices, herbs and other natural remedies, special diets, physical activity, and spiritual practices. In Norway, visits to alternative medicine providers, the use of natural remedies (including herbs), and self-help practices represent what people generally define as alternative medicine(link removed). The most commonly used alternative medicine modalities in the general population in Norway are natural remedies (47%), followed by self-help practices (29%) and therapies from alternative medicine providers (15%)(link removed).

Previous studies showed that 45% of Norwegian cancer patients use alternative medicine within the first 5 years of their cancer diagnosis(link removed)and that 33.4% of all cancer patients use alternative medicine annually(link removed). However, we do not know more about their consumption patterns, such as which therapies they use and for what purposes.

Young to middle-aged and highly educated female cancer patients have been described as the most frequent users of alternative medicine in Norway and elsewhere(link removed). Common use has also been reported in patients with symptoms related to their cancer with metastatic disease; received palliative care; and diagnosed with cancer more than three months ago(link removed). The most common reasons for the use of alternative medicine in cancer patients reported internationally are to increase the body's ability to fight the cancer, improve physical and emotional well-being, provide hope, and treat side effects and late and long-term effects of cancer and cancer treatment(link removed). Patients experienced the greatest benefits of alternative medicine for their physical and emotional well-being(link removed). Alternative medicine can also be used as a coping strategy(link removed).

The most commonly used alternative medicine modalities for cancer in Europe are the intake of substances considered to have curative potential (homeopathy, herbal treatment, etc.)(link removed). This is also the case in Norway, where 18% of cancer patients reported using “herbal or “natural” medicine” within a one-year period, compared to 14% who had consulted alternative medicine providers(link removed). Most cancer patients in Norway use alternative medicine in conjunction with conventional cancer treatment and are more likely to use conventional healthcare services than cancer patients who do not use alternative medicine(link removed).

Previous research shows that 65% of Norwegian hospitals offer some form of alternative medicine to complement conventional care(link removed). Additionally, most oncology healthcare providers demonstrate a positive attitude toward alternative medicine used as an adjunct to conventional cancer treatment(link removed). In some cases, they also use these therapies themselves. A national multicenter survey of Norwegian healthcare providers working in oncology departments found that approximately 20% of oncologists and 50% of nurses used some type of alternative medicine(link removed).. However, a 2016 national survey of oncology experts and alternative medicine providers found that the majority of doctors and nurses also believed that combining complementary and conventional cancer treatment carried risks (78% and 93%, respectively). The proportion of alternative medicine providers was significantly lower (43%)(link removed).

Cancer patients greatly value input from health care providers about alternative medicine(link removed). Ideally, they should feel free to discuss all options without fear of being rejected and/or stigmatized. This can best be achieved through open, transparent, nonjudgmental and informed discussions about possible outcomes of combining alternative medicine and conventional cancer treatment(link removed). However, only 18% of doctors and 26% of nurses working with cancer patients in Norway routinely ask patients about their alternative medicine use(link removed). In order to increase the dialogue between oncology healthcare providers and patients about their use of alternative medicine, in-depth and nuanced knowledge of not only the prevalence but also the patterns of alternative medicine use by cancer patients is required. To date, no research has been published assessing the patterns of alternative medicine use by cancer patients in Norway, and this article aims to fill this gap.

Objectives of the study

The objectives of this study were to map the various alternative medicine modalities that cancer patients use and to further investigate their reasons for use, communication about use, self-reported benefits and harms, and their sources of information about the various modalities.

Methods

In collaboration with the Norwegian Cancer Society (NCS), an online cross-sectional study was conducted among members of their user panel who currently have or have previously had cancer ( n = 706). The study was conducted between September 23 and October 12, 2021 using a modified, cancer-specific version of the International Questionnaire to Measure Use of Complementary and Alternative Medicine (I-CAM-Q).(link removed)carried out.

Participant

The NCS User Panel is a web panel of people with cancer experience, either as cancer patients or relatives of cancer patients, including survivors. The panel consists of 906 people, of which 706 people are currently suffering from cancer or have previously had cancer. The members are predominantly women (75%) and more than half are between 50 and 69 years old. Members are recruited through the NCS website, social media and a variety of social events.

All NCS user panel members aged 18 years and over with a current or previous cancer diagnosis were invited to participate in the survey. Members of the user panel who were relatives of someone who had, had, or died from cancer were excluded.

Recruitment and data collection

Panel members who met the inclusion criteria ( n = 706), received an email request from the NCS with a link to the survey. The first page of the survey was an information letter requiring participants to check “agree to participate” to proceed to the main survey. The survey was distributed exclusively online. A total of 10 emails were returned as undeliverable, resulting in 696 NCS user panel members receiving the invitation. A total of 478 members responded. However, ten did not consent to participate and were excluded from the study. Consequently, 468 agreed to participate, corresponding to a response rate of 67.2% (Fig. 1 ).

(link removed) Flowchart of participants(link removed)

Flowchart of participants(link removed)

Medium

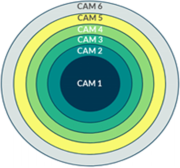

To compare alternative medicine use across different studies, the National Research Center for Complementary and Alternative Medicine (NAFCAM) in Norway developed the NAFCAM alternative medicine reporting model(link removed). In the model, alternative medicine activities were divided into six different levels; Alternative medicine level one represents more than three visits to one or more alternative medicine providers (not captured in the current study); Alternative Medicine Level 2 represents one or more visits to alternative medicine providers; Alternative Medicine Level 3 represents Alternative Medicine Level 2 and/or the use of natural remedies and/or self-help practices; Alternative Medicine Level 4 represents Alternative Medicine Level 3 and/or the use of special diets; Alternative medicine level 5 represents alternative medicine level 4 and/or the use of physical activity, while alternative medicine level 6 represents alternative medicine level 5 and/or the use of spiritual practices(link removed).

The I-CAM-Q was developed according to the NAFCAM model for classifying the use of alternative medicine(link removed)and included visits to alternative medicine providers, naturopathy, self-help practices, nutritional supplements, special diets, physical activity, and spiritual practices (see Tables 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, and 7 for the specific modalities queried in this particular study). Sociodemographic data such as income and education were also collected. Data on age, gender and cancer diagnosis were already collected by the NCS for all members when they logged into the user panel and were added to the survey questions for all participants. For all modalities used, participants were asked follow-up questions about the reasons for using alternative medicine ((1) treating/slowing the cancer or preventing the spread of the cancer; (2) treating side effects/late and long-term effects of the cancer or cancer treatment; (3) strengthening the body/immune system; (4) increasing quality of life, coping, relaxation or the well-being; (5) Other reasons) and possible side effects ((1) Yes, serious; (2) Yes, moderate; (3) Yes, mild; (4) No; (5) Don't know). Depending on the type of alternative medicine (e.g., alternative medicine providers; natural remedies; self-help practices; special diets; physical activity; spiritual practice), participants were asked how they experienced the possible effects of the modalities, with the following options: (1) experienced getting better; (2) No change; (3) became worse; and (4) Don't know. In addition, they were asked where they obtained the information about the modality/approach, with the following response categories: (1) internet/media; (2) healthcare providers (doctor/nurse etc.); (3) alternative medicine providers; (4) friends, family, etc.; (5) Other; (6) Don't remember/don't know; (7) did not receive/did not seek information, and further whether they had discussed this use of treatments with their: (1) general practitioner (GP); (2) oncologist; (3) nurse; (4) Other health care providers (nutritionists, etc.); (5) alternative medicine providers; (6) None of these; (7) Don't remember/don't know.

The NAFCAM alternative medicine reporting model

The NAFCAM Alternative Medicine Reporting Model is a six-tier model that describes the level of alternative medicine use with six cutoff points that would represent generally accepted levels of exposure to alternative medicine, with the next levels in the model always including the previous levels (see Table 8 for a visual description of the model).(link removed). The study was reported in accordance with the NAFCAM model(link removed)reporting use of alternative medicine since diagnosis in cancer patients at levels 2–6. Alternative medicine level 1 data (more than three visits to alternative medicine providers) could not be reported because the number of visits was not reported. Since alternative medicine is mostly considered alternative medicine at levels 2–3 in Norway, the associations for alternative medicine use are for alternative medicine level 2 (visits to alternative medicine providers) and level 3 (visits to alternative medicine providers and/or use of natural remedies, and/or self-help practices). Data on dietary changes and vitamin and mineral use were also collected and will be presented in a separate paper.

Measures of personal characteristics

Age was collected as an open question and assessed as a continuous variable and categorically after merging into the following groups; 19-50 years ; 51-64 years and 65 years or more .

Educational level was assessed using four categories: (1) primary school up to 10 years; (2) secondary school 10–12 years duration; (3) college/university less than 4 years duration; and (4) college/university of at least 4 years duration.

Household income was assessed using the following categories: NOK < 400,000 (low income); NOK 400,000-799,000 (middle income) and NOK 800,000 or more (high income) in addition to an option not to provide income information.

Further personal characteristics were gender (female, male) and place of residence (grouped into the Norwegian regions of South-East, South, West, Central (Trøndelag) and North).

Statistics/performance calculation

With a margin of error of 5%, a confidence level of 95%, and heterogeneity of 50%, we required a minimum sample of n = 384 to represent the Norwegian cancer population of 305,503 for sufficient study power(link removed). Descriptive statistics were performed using cross-tabulations and frequency analysis. For between-group analyses, Pearson chi-square tests and Fisher exact tests were used for categorical variables and binary logistic regression for adjusted values. Independent sample t tests were used for continuous variables. Significance levels were set p <0.05 set. Analyzes were performed using SPSS V.28.0 for Windows.

Results

NCS user panel members are composed of more women (75%) than men (25%), resulting in more women than men in the study (67% and 33%, p < 0.001) with an average age of 57.3 and 62.9 years ( p <0.001). The majority of participants had a college or university degree (63%), high income (46%), and lived in southeastern Norway (52%). Most participants lived with a spouse/partner (67%); However, more men (75%) than women (63%, p = 0.008, Table 1 ).

| In total | Women | Men | Alternative medicine level 2 (link removed) | Alternative medicine level 3 (link removed) | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| % | n = 468 | % | n = 315 | % | n = 153 | % | n = 143 | p -Value | % | n = 346 | p -Value | ||

| sex | < 0.001* | < 0.001* | 0.002* | ||||||||||

| Women | 67.3 | 315 | 38.9 | 114 | 83.1 | 246 | |||||||

| Men | 32.7 | 153 | 20.3 | 29 | 69.9 | 100 | |||||||

| The age | < 0.001* | 0.043* | 0.735* | ||||||||||

| 19-50 years | 23.1 | 100 | 27.9 | 81 | 13.3 | 19 | 35.0 | 35 | 81.0 | 81 | |||

| 51-64 years | 41.3 | 179 | 43.4 | 126 | 37.1 | 53 | 38.0 | 68 | 77.1 | 138 | |||

| 65 years or more | 35.6 | 154 | 28.6 | 83 | 49.7 | 71 | 25.3 | 39 | 79.2 | 122 | |||

| Mean age (SD) | 59.2 (11,295) | 57.3 (11,277) | 62.9 (10,408) | <0.001′ | 57.36 (10.713) | 0.019’ | 59.0 (11,451) | 0.511’ | |||||

| training | 0.319* | 0.003* | < 0.001* | ||||||||||

| Primary school (less than 10 years) | 6.5 | 28 | 5.2 | 15 | 9.1 | 13 | 3.6 | 1 | 46.4 | 13 | |||

| Secondary school (10–12 years) | 28.0 | 131 | 29.3 | 85 | 32.2 | 46 | 32.8 | 43 | 80.9 | 106 | |||

| University less than 4 years | 33.9 | 147 | 35.9 | 104 | 30.1 | 43 | 39.5 | 58 | 81.0 | 119 | |||

| University 4 years or more | 29.3 | 127 | 29.7 | 86 | 28.7 | 41 | 31.5 | 40 | 81.1 | 103 | |||

| Household income | 0.477* | 0.242* | 0.074* | ||||||||||

| Low (less than 400,000 NOK) | 10.4 | 45 | 10.4 | 45 | 10.3 | 30 | 10.5 | 15 | 73.3 | 33 | |||

| Medium (NOK 400,000 – 799,000) | 35.1 | 152 | 35.1 | 152 | 35.9 | 104 | 33.6 | 48 | 73.0 | 111 | |||

| High (800,000 NOK or more) | 46.4 | 201 | 46.4 | 201 | 44.5 | 129 | 50.3 | 72 | 83.6 | 168 | |||

| Didn't answer | 8.1 | 35 | 8.1 | 35 | 9.3 | 27 | 5.6 | 8 | 82.9 | 29 | |||

| Household** | |||||||||||||

| Live alone | 20.7 | 97 | 9/22 | 72 | 16.3 | 25 | 0.103* | 36.1 | 35 | 0.435* | 75.3 | 73 | 0.331* |

| Live with a partner | 66.9 | 313 | 62.9 | 198 | 75.2 | 115 | 0.008* | 32.3 | 101 | 0.707* | 80.2 | 251 | 0.266* |

| Live with your own children | 18.2 | 85 | 21.3 | 67 | 11.8 | 18 | 0.012* | 36.5 | 31 | 0.441* | 85.9 | 73 | 0.076* |

| Miscellaneous | 1.5 | 7 | 1.6 | 5 | 1.3 | 2 | 1,000^ | 14.3 | 1 | 0.435^ | 85.7 | 6 | 1,000^ |

| Place of residence (region) | 0.460* | 0.497* | 0.737* | ||||||||||

| Southeast | 51.7 | 242 | 53.3 | 168 | 48.4 | 74 | 30.6 | 71 | 78.9 | 183 | |||

| south | 4.3 | 20 | 4.1 | 13 | 4.6 | 7 | 40.0 | 8 | 85.0 | 17 | |||

| west | 24.8 | 116 | 22.5 | 71 | 29.4 | 45 | 30.5 | 32 | 75.7 | 81 | |||

| Center (Trøndelag) | 8.5 | 40 | 8.3 | 26 | 9.2 | 14 | 41.2 | 14 | 77.1 | 27 | |||

| north | 10.7 | 50 | 11.7 | 37 | 8.5 | 13 | 40.0 | 18 | 84.4 | 37 | |||

*Pearson chi-square test; ^Fisher's exact test; 'Independent sample t-test; (link removed) Alternative Medicine Level 2: One or more visits to alternative medicine providers; (link removed) Alternative Medicine Level 3: One or more visits to alternative medicine providers, use of alternative medicine natural remedies and/or alternative medicine self-help practices; **Multiple selection

More than half of the women suffered from breast cancer (58%), followed by female genital cancer (12%) and gastrointestinal cancer (11%). In men, however, genital cancer was most commonly diagnosed (34%), followed by gastrointestinal cancer (20%) and lymphoma (14%). Approximately one-third of participants (34%) were undergoing active cancer treatment at the time of the survey (Table 2 ). A total of 12% had cancer in more than one site.

Associations for alternative medicine use

The clearest indicator of alternative medicine use was female gender, as women were significantly more likely to use alternative medicine than men, 39% versus 20% (Alternative Medicine Level 2) and 83% versus 70% (Alternative Medicine Level 3, p <0.003). Participants with the lowest level of education (primary school) were less likely to use alternative medicine ( p < 0.004, Table 1 ). Those who visited alternative medicine providers (alternative medicine level 2) were more likely to be middle-aged (51-64 years, p = 0.043, Table 1 ). Both breast cancer and skin cancer were indicators of high use of alternative medicine; but not gender adjusted. This was also true for male genital cancer, which indicated low use of alternative medicine (Table 2 ).

| In total | Women | Men | Alternative medicine level 2 (link removed) | Alternative medicine level 3 (link removed) | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| % | n = 468 | % | n = 315 | % | n = 153 | % | n = 143 | p -Value | % | n = 346 | p -Value | ||

| Cancer site** | |||||||||||||

| Breast | 39.1 | 183 | 57.8 | 172 | 0.7 | 1 | < 0.001* | 42.0 | 71 | 0.001* | 80.7 | 138 | 0.474* |

| Gastrointestinal | 13.7 | 64 | 10.5 | 33 | 20.3 | 31 | 0.004* | 22.6 | 14 | 0.064* | 79.0 | 49 | 0.964* |

| Male sexual organ | 11.1 | 52 | 0.0 | 0 | 34.0 | 52 | < 0.001* | 18.2 | 9 | 0.028* | 62.5 | 30 | 0.003* |

| Lymphoma | 8.8 | 41 | 6.3 | 20 | 13.7 | 21 | 0.008* | 25.6 | 10 | 0.318* | 74.4 | 29 | 0.537* |

| Female genitals | 8.1 | 38 | 12.1 | 38 | 0.0 | 0 | < 0.001* | 41.7 | 15 | 0.237* | 91.7 | 33 | 0.049* |

| Malignant melanoma | 4.7 | 22 | 4.4 | 14 | 5.2 | 8 | 0.707* | 27.3 | 6 | 0.571* | 72.7 | 16 | 0.433^ |

| head and neck | 3.8 | 18 | 1.6 | 5 | 8.5 | 16 | < 0.001* | 23.5 | 4 | 0.448* | 82.4 | 14 | 1,000^ |

| lung | 3.2 | 15 | 2.5 | 8 | 4.7 | 7 | 0.268^ | 26.7 | 4 | 1,000^ | 78.6 | 11 | 1,000^ |

| sarcoma | 3.0 | 14 | 3.8 | 12 | 1.3 | 2 | 0.160^ | 35.7 | 5 | 0.779^ | 85.7 | 12 | 0.744^ |

| skin | 2.4 | 11 | 2.5 | 8 | 2.0 | 3 | 1,000^ | 20.0 | 2 | 0.509* | 50.0 | 5 | 0.039^ |

| leukemia | 2.4 | 11 | 2.2 | 7 | 2.6 | 4 | 0.755^ | 27.3 | 3 | 1,000^ | 72.7 | 8 | 0.707^ |

| Bone marrow | 2.1 | 10 | 1.9 | 6 | 2.6 | 4 | 0.735^ | 50.0 | 5 | 0.308^ | 100 | 10 | 0.129^ |

| Brain tumor | 1.9 | 9 | 0.6 | 2 | 4.6 | 7 | 0.007^ | 33.3 | 2 | 1,000^ | 100 | 6 | 0.350^ |

| thyroid | 1.9 | 9 | 2.5 | 8 | 0.7 | 1 | 0.163* | 50.0 | 4 | 0.448^ | 87.5 | 7 | 1,000^ |

| bubble | 1.7 | 8 | 0.3 | 1 | 4.6 | 7 | 0.002^ | 0.0 | 0 | 0.057^ | 75.0 | 6 | 0.679^ |

| kidney | 1.3 | 6 | 0.3 | 1 | 3.3 | 5 | 0.016^ | 40.0 | 2 | 0.665^ | 100 | 5 | 0.589^ |

| liver | 1.1 | 5 | 0.6 | 2 | 2.0 | 3 | 0.336^ | 50.0 | 2 | 0.600^ | 100 | 5 | 0.589^ |

| esophagus | 1.1 | 5 | 0.3 | 1 | 2.6 | 4 | 0.041^ | 0.0 | 0 | 0.177^ | 60.0 | 3 | 0.287* |

| pancreas | 0.6 | 3 | 0.3 | 1 | 1.3 | 2 | 0.250^ | 0.0 | 0 | 0.554^ | 66.7 | 2 | 0.511^ |

| Gallbladder | 0.6 | 3 | 0.6 | 2 | 0.7 | 1 | 1,000^ | 0.0 | 0 | 1,000^ | 66.7 | 2 | 0.511* |

| Neuroendocrines | 0.4 | 2 | 0.6 | 2 | 0.0 | 0 | 1,000^ | 50.0 | 1 | 0.549^ | 100 | 2 | 1,000^ |

| Other cancer sites | 2.1 | 10 | 2.9 | 9 | 0.7 | 1 | 0.177^ | 30.0 | 3 | 1,000^ | 90.0 | 9 | 0.696* |

| In active cancer treatment | 0.332* | 0.302* | 0.055* | ||||||||||

| Yes | 33.8 | 158 | 35.2 | 111 | 30.7 | 47 | 36.0 | 54 | 84.0 | 126 | |||

| No | 66.2 | 310 | 64.8 | 204 | 69.3 | 106 | 31.1 | 89 | 76.1 | 220 | |||

(link removed) Alternative Medicine Level 2: One or more visits to alternative medicine providers; (link removed) Alternative Medicine Level 3: One or more visits to alternative medicine providers, use of alternative medicine natural remedies, and/or use of alternative medicine self-care practices; *Pearson chi-square test; ^Fisher's exact test; **The cancer may be placed in more than one location

Visits to alternative medicine providers

Of the 468 participants, 436 answered the questions about the modalities of alternative medicine providers. Of these, 33% attended ( n = 143) alternative medicine providers to receive one or more of the modalities listed in Table 3 in the period following their initial cancer diagnosis, 30% ( n = 43) used more than one modality with a mean of 1.5 different provider-based alternative medicine modalities (range 1-6). The most commonly used alternative medicine modality was Massage/Aromatherapy , which is from 19% ( n = 84) was used, followed by acupuncture (11%, n = 48), Osteopathy (4%, n = 18), Naprapathy (4%, n = 18) , andcure (4%, n = 17). Most participants visited alternative medicine providers for reasons of well-being and to improve quality of life (64%, n = 91) or to treat side effects/late and long-term consequences of their cancer/cancer treatment (59%, n = 85). Only 10 participants (7%) had used the modalities to treat the cancer or prevent its spread; Heal ( n = 5), Herbal therapy ( n = 2), acupuncture ( n = 2) and homeopathy ( n = 1). Very few (8%, n = 11) experienced side effects after seeing an alternative medicine provider, primarily fromacupuncture ( n = 5; 4 mild and 1 moderate) and massage ( n = 3; 1 mild and 2 moderate, Table 3 ).

| Reason(s) for use (multiple selection) | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| In total | Women | Men | p -Value | To treat cancer or prevent it from spreading | To treat side effects or long-term effects of cancer/cancer treatments | To strengthen the body/immune system | To increase the quality of life, to cope, relax or feel good | Other reasons | Side effects of treatment | |

| % (n) | % (n) | % (n) | % (n) | % (n) | % (n) | % (n) | % (n) | % (n) | ||

| Massage/Aromatherapy | 19.3 (84) | 23.9 (70) | 9.8 (14) | < 0.001* | 0.0 (0) | 56.0 (47) | 22.6 (19) | 78.6 (66) | 0.0 (0) | 3.6 (3) |

| acupuncture | 11.0 (48) | 13.3 (39) | 6.3 (9) | 0.028* | 4.2 (2) | 70.8 (34) | 29.2 (14) | 47.9 (23) | 12.5 (6) | 10.4 (5) |

| Naprapathy | 4.1 (18) | 3.8 (11) | 4.9 (7) | 0.574* | 0.0 (0) | 55.6 (10) | 33.3 (6) | 55.6 (10) | 33.3 (6) | 11.1 (2) |

| Osteopathy | 4.1 (18) | 5.8 (17) | 0.7 (1) | 0.012* | 0.0 (0) | 83.3 (15) | 22.2 (4) | 44.4 (8) | 16.7 (3) | 0.0 (0) |

| cure | 3.9 (17) | 4.4 (13) | 2.8 (4) | 0.406* | 29.4 (5) | 23.5 (4) | 17.6 (3) | 67.7 (11) | 5.9 (1) | 5.9 (1) |

| Reflexology | 2.3 (10) | 3.4 (10) | 0.0 (0) | 0.035^ | 0.0 (0) | 50.0 (5) | 80.0 (8) | 60.0 (6) | 20.0 (2) | 10.0 (1) |

| Coaching | 2.3 (10) | 3.1 (9) | 0.7 (1) | 0.177^ | 0.0 (0) | 10.0 (1) | 0.0 (0) | 100 (10) | 10.0 (1) | 10.0 (1) |

| homeopathy | 1.8 (8) | 2.7 (8) | 0.0 (0) | 0.057^ | 12.5 (1) | 50.0 (4) | 50.0 (4) | 25.0 (2) | 37.5 (2) | 12.5 (1) |

| Herbal therapy | 0.9 (4) | 1.4 (4) | 0.0 (0) | 0.309^ | 50.0 (2) | 75.0 (3) | 75.0 (3) | 50.0 (2) | 0.0 (0) | 25.0 (1) |

| Rose therapy | 0.2 (1) | 0.3 (1) | 0.0 (0) | 1,000^ | 0.0 (0) | 0.0 (0) | 0.0 (0) | 100 (1) | 0.0 (0) | 0.0 (0) |

| Other provider-based therapies (link removed) | 17.5 (75) | 20.6 (59) | 11.3 (16) | 0.016* | – | – | – | – | – | – |

| Consultations with alternative medicine providers | 32.8 (143) | 38.9 (114) | 20.3 (29) | < 0.001* | 7.0 (10) | 59.4 (85) | 30.1 (43) | 63.6 (91) | 9.1 (13) | 7.7 (11) |

(link removed) Pearson chi-square test; ^Fisher's exact test; (link removed) Not included in overall alternative medicine because it is uncertain whether it is alternative medicine;–not raised

Most participants found the treatments beneficial (87%, n = 125), and none experienced worsening of symptoms due to the treatments. 43% of participants learned about provider-based alternative medicine from healthcare providers (43%, n = 62), followed by family/friends (34%, n = 49), Internet/Media (25%, n = 36) or from alternative medicine providers (13%, n = 19). 14% ( n = 20) consulted other sources, while 7% ( n = 10) did not obtain information about the modalities they used. Regarding discussing alternative medicine provider visits with healthcare providers, 46% ( n = 66) said they had talked to their family doctor about it, 30% ( n = 43) with their oncologist, 13% ( n = 18) with a nurse, 8% ( n = 11) with an alternative medicine provider and 19% ( n = 27) had discussed the application with other healthcare providers. 32 percent ( n = 45) had not discussed this with any of the providers mentioned above. Multiple responses were possible for information and communication (Table 4 ).

| Alternative medicine providers | Natural remedies | Self-help practices | Special diets | Physical activity | Spiritual practices | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| % ( n = 143) | % ( n = 230) | % ( n = 253) | % ( n = 13) | % ( n = 405) | % ( n = 132) | |

| Self-reported effect* | ||||||

| Better | 87.4 (125) | 34.5 (79) | 80.6 (204) | 46.2 (2) | 83.1 (325) | 28.9 (37) |

| No change | 7.7 (11) | 41.5 (95) | 10.3 (26) | 7.7 (1) | 10.0 (39) | 45.3 (58) |

| Worse | 0.0 (0) | 0.0 (0) | 0.0 (0) | 0.0 (0) | 1.0 (4) | 0.0 (0) |

| I don't know | 4.9 (7) | 24.0 (55) | 9.1 (23) | 46.2 (6) | 5.9 (23) | 25.8 (33) |

| Information** | ||||||

| Internet/Media | 25.2 (36) | 45.7 (105) | 34.4 (87) | 61.5 (8) | 23.7 (96) | 0.9 (4) |

| Healthcare providers | 43.4 (62) | 19.6 (45) | 38.3 (97) | 7.7 (1) | 39.0 (158) | 0.8 (1) |

| Alternative medicine providers | 13.3 (19) | 7.4 (17) | 6.3 (16) | 23.1 (3) | 3.0 (12) | 0.8 (1) |

| friends family | 34.3 (49) | 28.3 (65) | 28.5 (72) | 38.5 (5) | 24.7 (100) | 29.5 (39) |

| Miscellaneous | 14.0 (20) | 18.3 (42) | 20.6 (52) | 15.4 (2) | 19.0 (77) | 21.2 (28) |

| Don't know anymore | 5.6 (8) | 5.2 (12) | 6.3 (16) | 0.0 (0) | 7.4 (30) | 3.0 (4) |

| Not searched/received | 7.0 (10) | 12.6 (29) | 15.4 (39) | 0.0 (0) | 24.7 (100) | 43.9 (58) |

| Communication** | ||||||

| Family doctor | 46.2 (66) | 21.3 (49) | 32.8 (83) | 7.7 (1) | 41.2 (167) | 0.8 (1) |

| oncologist | 30.1 (43) | 17.0 (39) | 24.5 (62) | 38.5 (5) | 29.1 (118) | 0.0 (0) |

| Nurse | 12.6 (18) | 5.7 (13) | 16.2 (41) | 7.7 (1) | 14.8 (60) | 1.5 (2) |

| Alternative medicine providers | 7.7 (11) | 10.9 (25) | 16.6 (42) | 23.1 (3) | 0.0 (0) | 0.8 (1) |

| Other healthcare providers | 18.9 (27) | 5.7 (13) | 5.9 (15) | 23.1 (3) | 17.3 (70) | 0.8 (1) |

| None of these | 31.5 (45) | 55.2 (127) | 41.1 (104) | 46.2 (6) | 32.6 (132) | 88.6 (117) |

| Don't know anymore | 3.5 (5) | 4.8 (11) | 4.3 (11) | 0.0 (0) | 5.9 (24) | 4.5 (6) |

(link removed) Due to missing answers, the numbers do not always add up to the total; **Multiple selection

Use of natural remedies

Of the 468 participants, 441 answered the questions about natural remedies. Of these, 52% ( n = 230), one or more of those in table 5 listed natural remedies, 60% of which ( n = 138) used more than one remedy, with a mean of 2.4 remedies used (range 1–10). . The most commonly used remedy was Omega 3, 6, 9 fatty acids (31%, n = 138), followed by Ginger (20%, n = 86), green tea and Blueberries/bilberry extract (both 17%, n = 74). ). Most natural remedies were used to strengthen the body or immune system (90%, n = 207), while 39% (n = 90) used it with the intention of increasing quality of life, coping, relaxation or well-being. However, 20% use it to treat the cancer or prevent it from spreading, and 24% use it to manage side effects/late and long-term effects of cancer/cancer treatments. Few (6%, n = 17) experienced side effects from natural remedies, mainly from Omega 3, 6, 9 fatty acids (5 mild and 1 moderate, Table 5 ).

| Reason(s) for use (multiple selection) | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| In total | Women | Men | p -Value | To treat cancer or prevent it from spreading | To treat side effects or long-term effects of cancer/cancer treatments | To strengthen the body/immune system | To increase the quality of life, to cope, relax or feel good | Other reasons | Side effects of treatment | |

| % (n) | % (n) | % (n) | % (n) | % (n) | % (n) | % (n) | % (n) | % (n) | ||

| Omega 3, 6, 9 fatty acids | 31.3 (138) | 31.3 (93) | 31.3 (45) | 0.937* | 8.0 (11) | 18.8 (26) | 90.6 (125) | 26.1 (36) | 2.2 (3) | 4.3 (6) |

| Ginger | 19.5 (86) | 23.2 (69) | 11.8 (17) | 0.007* | 16.3 (14) | 20.9 (18) | 80.2 (69) | 34.9 (30) | 12.8 (11) | 1.2 (1) |

| Green tea | 16.8 (74) | 19.5 (58) | 11.1 (16) | 0.040* | 17.6 (13) | 13.5 (10) | 79.2 (59) | 51.4 (38) | 4.1 (3) | 4.1 (3) |

| Blueberries / blueberry extract | 16.8 (74) | 18.5 (55) | 13.2 (19) | 0.169* | 14.9 (11) | 12.2 (9) | 97.3 (72) | 23.0 (17) | 6.6 (5) | 4.1 (3) |

| Garlic | 15.2 (67) | 13.8 (41) | 18.1 (26) | 0.231* | 17.9 (12) | 13.4 (9) | 89.6 (60) | 28.4 (19) | 10.4 (7) | 3.0 (2) |

| Turmeric / Curcumin | 11.4 (50) | 12.8 (38) | 8.3 (12) | 0.201* | 40.0 (20) | 30.0 (15) | 80.0 (40) | 32.0 (16) | 2.0 (1) | 4.0 (2) |

| Aloe vera | 3.9 (17) | 3.7 (11) | 4.2 (6) | 0.807* | 5.9 (1) | 35.3 (6) | 35.3 (6) | 41.2 (7) | 17.6 (3) | 11.8 (2) |

| Chaga | 3.2 (14) | 4.4 (13) | 0.7 (1) | 0.043^ | 57.1 (8) | 14.3 (2) | 64.3 (9) | 14.3 (2) | 7.1 (1) | 7.1 (1) |

| Echinacea | 1.6 (7) | 2.0 (6) | 0.7 (1) | 0.435* | 14.3 (1) | 14.3 (1) | 85.7 (6) | 14.3 (1) | 0.0 (0) | 14.3 (1) |

| Q10 | 1.6 (7) | 2.0 (6) | 0.7 (1) | 0.435* | 0.0 (0) | 42.9 (3) | 85.7 (6) | 28.6 (2) | 14.3 (1) | 14.3 (1) |

| ginseng | 0.9 (4) | 1.0 (3) | 0.7 (1) | 0.605^ | 25.0 (1) | 25.0 (1) | 100 (4) | 50.0 (2) | 0.0 (0) | 25.0 (1) |

| Medicinal mushrooms (reishi, maitake, shiitake) | 0.7 (3) | 0.7 (2) | 0.7 (1) | 1,000^ | 66.7 (2) | 33.3 (1) | 100 (3) | 33.3 (1) | 0.0 (0) | 0.0 (0) |

| cannabis | 0.7 (3) | 0.3 (1) | 1.4 (2) | 0.250^ | 0.0 (0) | 0.0 (0) | 33.3 (1) | 33.3 (1) | 33.3 (1) | 0.0 (0) |

| Noni juice | 0.7 (3) | 0.7 (2) | 0.7 (1) | 1,000^ | 33.3 (1) | 66.7 (2) | 100 (3) | 0.0 (0) | 0.0 (0) | 0.0 (0) |

| Birch sap | 0.5 (2) | 0.3 (1) | 0.7 (1) | 0.545^ | ||||||

| Mistletoe/Iscador | 0.5 (2) | 0.7 (2) | 0.0 (0) | 0.455^ | 100 (2) | 0.0 (0) | 50.0 (1) | 0.0 (0) | 0.0 (0) | 50.0 (1) |

| Evening primrose oil | 0.5 (2) | 0.7 (2) | 0.0 (0) | 0.455^ | 50.0 (1) | 0.0 (0) | 0.0 (0) | 50.0 (1) | 0.0 (0) | 0.0 (0) |

| Rose root | 0.5 (2) | 0.7 (2) | 0.0 (0) | 0.452^ | 0.0 (0) | 50.0 (1) | 50.0 (1) | 100 (2) | 0.0 (0) | 0.0 (0) |

| Shark cartilage | 0.2 (1) | 0.3 (1) | 0.0 (0) | 0.673^ | 0.0 (0) | 100 (1) | 100 (1) | 0.0 (0) | 0.0 (0) | 0.0 (0) |

| Milk thistle | 0.0 (0) | 0.0 (0) | 0.0 (0) | – | – | – | – | – | – | – |

| Other natural remedies (link removed) | 6.8 (30) | 8.4 (25) | 3.5 (5) | 0.084* | – | – | – | – | – | – |

| Use of natural remedies | 52.2 (230) | 53.5 (159) | 49.3 (71) | 0.418 | 20.0 (46) | 23.9 (55) | 90.0 (207) | 39.1 (90) | 12.2 (28) | 6.1 (17) |

(link removed) Pearson chi-square test; ^Fisher's exact test; (link removed) Not included in all natural remedies as it is not alternative medicine; –not collected

About a third of participants experienced that the remedies were beneficial to them (35%, n = 79), and 42% ( n = 95) experienced no change from the natural remedies. None experienced worsening of their symptoms due to the agents (Table 4).

Almost half of the participants (46%, n = 105) collected information about natural remedies from the Internet or the media, while 28% ( n = 65) sought or received information from family and friends. Twenty percent ( n = 45) received information from healthcare providers and 7% ( n = 17) from alternative medicine providers. 18% ( n = 42) used other sources and 13% ( n = 29) did not obtain any information. Total 21% ( n = 49) reported the use of natural remedies to their family doctor, 17% ( n = 39) their oncologist, 6% ( n = 13) a nurse; 11% ( n = 25) to an alternative medicine provider, while 6% ( n = 13) discussed the application with other healthcare providers. More than half of natural remedy users (55%, n = 127) did not disclose their use to any of the above providers (Table 4).

Self-help practices

Of the 468 participants, 437 answered questions about self-help practices. Of these, 58% ( n = 253), one or more of those in table 6 to have used the self-help practices listed. More than one self-help practice was used by 66% ( n = 166) used, with a mean of 2.2 self-help practices used (range 1–6). Almost half of the participants (49%, n = 213). Relaxation techniques , followed by meditation (29%, n = 127) and yoga (28%, n = 122), mainly to increase quality of life (94%, n = 200, n = 119 and n = 115 respectively). Few people experienced side effects from self-help practices (6%, n = 16, Table 6 ), mainly from Relaxation techniques ( n = 11), meditation ( n = 8) and yoga ( n = 7). Most side effects were mild or moderate, but two were reported as serious, one through yoga and one through Art therapy . The majority (81%, n = 204) found the practices helpful (Table 4). None experienced worsening of their symptoms. A third of participants learned about self-care practices from healthcare providers (38%, n = 97), followed by Internet/Media (34%, n = 87) and friends and family (29%, n = 72). Only a few received information from alternative medicine providers (6%, n = 16). Fifteen percent ( n = 39) did not seek or receive information about the practices used (Table 4 ). When it comes to discussing self-care practices with healthcare providers, 33% ( n = 83) said they had spoken to their family doctor about it, 25% ( n = 62) with their oncologist, 16% ( n = 41) with a nurse, 17% (n = 42) with an alternative medicine provider, while 6% ( n = 15) had discussed the practices with other healthcare providers. 41 percent ( n = 104) had not discussed this with any of the providers mentioned above (Table 4 ).

| Reason(s) for use (multiple selection) | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| In total | Women | Men | p -Value | To treat cancer or prevent it from spreading | To treat side effects or long-term effects of cancer/cancer treatments | To strengthen the body/immune system | To increase the quality of life, to cope, relax or feel good | Other reasons | Side effects of treatment | |

| % ( n ) | % (n) | % (n) | % (n) | % (n) | % (n) | % (n) | % (n) | % (n) | ||

| relaxation | 48.7 (213) | 55.8 (164) | 34.3 (49) | < 0.001* | 5.2 (11) | 33.8 (72) | 36.6 (78) | 93.9 (200) | 1.4 (3) | 5.2 (11) |

| Meditation/Mindfulness | 29.1 (127) | 38.1 (112) | 10.5 (15) | < 0.001* | 7.1 (9) | 38.6 (49) | 39.4 (50) | 93.7 (119) | 4.7 (6) | 5.5 (8) |

| yoga | 27.9 (122) | 38.1 (112) | 7.0 (10) | < 0.001* | 4.1 (5) | 45.1 (55) | 57.4 (70) | 94.3 (115) | 5.7 (7) | 5.7 (7) |

| Visualization | 7.1 (31) | 9.2 (27) | 2.8 (4) | 0.015* | 9.6 (3) | 22.6 (7) | 35.5 (11) | 93.5 (29) | 9.7 (3) | 6.5 (2) |

| Music therapy | 5.0 (22) | 4.4 (13) | 6.3 (9) | 0.410* | 0.0 (0) | 18.2 (4) | 9.1 (2) | 95.5 (21) | 13.6 (3) | 4.5 (1) |

| Tai Chi/Qigong | 4.1 (18) | 5.4 (16) | 1.4 (2) | 0.046* | 5.6 (1) | 33.3 (6) | 61.1 (11) | 94.4 (17) | 0.0 (0) | 11.1 (2) |

| Art therapy | 2.3 (10) | 3.4 (10) | 0.0 (0) | 0.035^ | 0.0 (0) | 30.0 (3) | 20.0 (2) | 90.0 (9) | 20.0 (2) | 1.0 (1) |

| Astrology/Numerology/Soothsayers | 0.9 (4) | 1.4 (4) | 0.0 (0) | 0.308^ | 0.0 (0) | 0.0 (0) | 0.0 (0) | 75.0 (3) | 25.0 (1) | 0.0 (0) |

| Other self-help practices (link removed) | 26.1 (114) | 27.9 (82) | 22.4 (32) | 0.210* | – | – | – | – | – | – |

| Self-help practices | 57.9 (253) | 66.3 (195) | 40.6 (58) | <0.001* | 6.3 (16) | 39.9 (101) | 46.2 (117) | 96.0 (243) | 5.9 (15) | 6.3 (16) |

(link removed) Pearson chi-square test; ^Fisher's exact test; (link removed) not included in general alternative medicine self-help practices because the uncertainty that it is alternative medicine is not raised

Special diets

Very few participants (3%, n = 13) had used special diets, only 5 men and 8 women ( p = 0.766). Two different diets have been reported; Juice diet (2%, n = 8) and Budwig diet (a diet consisting of a special lacto-vegetarian diet with a mixture of oil and protein(link removed), 1%, n = 6). All but one participant had used only one specific diet (86%), resulting in a mean of 1.1 diets used (range 1–2). These diets were mainly used to treat the cancer or prevent it from spreading (85%, n = 11) or to strengthen the body and the immune system (77%, n = 10). Two people experienced improvements after using the diets, and no one experienced worsening of their symptoms (Table 4). However, 4 of 8 participants (50%) experienced side effects Juice diet on: 1 moderate and 3 mild side effects were reported (Table 7). Most participants who had used special diets found information about these diets on the Internet or in the media (62%, n = 8), and 54% had discussed use with healthcare providers, primarily their oncologist (39% , n = 8). n = 5, Table 4 ).

| Reason(s) for use (multiple selection) | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| In total | Women | Men | p-value | To treat cancer or prevent it from spreading | To treat side effects or long-term effects of cancer/cancer treatments | To strengthen the body/immune system | To increase the quality of life, to cope, relax or feel good | Other reasons | Side effects of treatment | |

| % (n) | % (n) | % (n) | % (n) | % (n) | % (n) | % (n) | % (n) | % (n) | ||

| Special diets | 2.9 (13) | 2.7 (8) | 3.4 (5) | 0.766^ | 84.6 (11) | 38.4 (5) | 76.9 (10) | 38.4 (5) | 0.0 (0) | 30.8 (4) |

| Juice diet (carrot, beetroot, apricot, etc.) | 1.8 (8) | 1.7 (5) | 2.0 (3) | 0.723^ | 62.5 (5) | 50.0 (4) | 87.5 (7) | 50.0 (4) | 0.0 (0) | 50.0 (4) |

| Breuss diet | 0.0 (0) | 0.0 (0) | 0.0 (0) | – | – | – | – | – | – | – |

| Budwig diet | 1.3 (6) | 1.3 (4) | 1.4 (2) | 1,000^ | 100 (6) | 16.6 (1) | 66.7 (4) | 16.6 (1) | 0.0 (0) | 0.0 (0) |

| Gerson therapy | 0.0 (0) | 0.0 (0) | 0.0 (0) | – | – | – | – | – | – | – |

| Macrobiotic diet | 0.0 (0) | 0.0 (0) | 0.0 (0) | – | – | – | – | – | – | – |

| Ornish diet | 0.0 (0) | 0.0 (0) | 0.0 (0) | – | – | – | – | – | – | – |

| Physical activity | 93.3 (405) | 92.8 (270) | 94.4 (135) | 0.525* | 8.9 (36) | 44.9 (182) | 73.6 (298) | 91.6 (372) | 8.9 (36) | 11.4 (46) |

| Nature walks | 84.3 (366) | 84.9 (247) | 83.2 (119) | 0.591* | 7.1 (26) | 37.2 (136) | 69.1 (253) | 92.9 (340) | 3.0 (11) | – |

| Walks along the street | 74.9 (325) | 76.6 (222) | 72.0 (103) | 0.360* | 5.5 (18) | 35.7 (116) | 64.9 (211) | 78.8 (256) | 5.5 (18) | – |

| Gym | 42.4 (184) | 43.0 (125) | 41.3 (59) | 0.737* | 8.7 (16) | 45.1 (83) | 78.3 (144) | 83.7 (154) | 4.9 (9) | – |

| Tailored training program | 41.5 (180) | 45.4 (132) | 33.6 (48) | 0.016* | 6.7 (12) | 51.1 (92) | 78.9 (142) | 87.2 (157) | 5.6 (10) | – |

| Skiing (cross-country skiing, slalom) | 26.3 (114) | 26.5 (77) | 25.9 (37) | 0.848* | 9.6 (11) | 39.4 (45) | 71.1 (81) | 94.7 (108) | 8.8 (10) | – |

| Jogging/running | 21.2 (92) | 21.0 (61) | 21.7 (31) | 0.836* | 12.0 (11) | 47.8 (44) | 84.8 (78) | 93.5 (86) | 5.4 (5) | – |

| Ball games (e.g. football, handball) | 1.6 (7) | 1.0 (3) | 2.8 (4) | 0.224^ | 0.0 (0) | 14.3 (1) | 85.7 (6) | 100 (7) | 14.3 (1) | – |

| Other physical activities | 48.2 (209) | 50.2 (146) | 44.1 (63) | 0.240* | – | – | – | – | – | – |

| Spiritual practices | 30.4 (132) | 32.3 (94) | 26.6 (38) | 0.267* | 31.8 (42) | 12.9 (17) | 9.8 (13) | 44.7 (59) | 42.4 (56) | 1.6 (2) |

| Pray for yourself | 19.6 (85) | 20.6 (60) | 17.5 (25) | 0.429* | 16.5 (14) | 8.2 (7) | 9.4 (8) | 55.3 (47) | 42.4 (36) | – |

| Prayed by others | 19.6 (85) | 20.6 (60) | 17.5 (25) | 0.471* | 42.4 (36) | 16.5 (14) | 8.2 (7) | 25.9 (22) | 37.6 (32) | – |

| Attending religious gatherings | 3.9 (17) | 3.4 (10) | 4.9 (7) | 0.470* | 0.0 (0) | 0.0 (0) | 0.0 (0) | 76.5 (13) | 35.3 (6) | – |

| Contact religious healer | 0.7 (3) | 0.3 (1) | 1.4 (2) | 0.254^ | 66.7 (2) | 33.3 (1) | 0.0 (0) | 66.7 (2) | 0.0 (0) | – |

| Shamanism | 0.0 (0) | 0.0 (0) | 0.0 (0) | – | – | – | – | – | – | – |

| Other spiritual practices | 3.2 (14) | 3.1 (9) | 3.5 (5) | 0.782^ | – | – | – | – | – | – |

*Pearson chi-square test; ^Fisher Exact Test;–not raised

Physical activity

Most participants (93%, n = 405) were physically active, of which 95% ( n = 383) were involved in more than one activity with an average of 3.6 different physical activities (range 1–7). The motivations for physical activity were mostly to increase quality of life, cope with illness, relax or improve well-being (92%, n = 372) or strengthening the body and immune system (74%, n = 298). The most common activities were Walks (88%, n = 381), either in nature (84%, n = 366) or along the street (75%, n = 325), but also visits in the gym (42%, n = 325). = 184) and customized training programs (42%, n = 180) were popular activities (Table 7). Most participants found that these activities improved their health (83%, n = 325, Table 4 ). Some (11%, n = 46, Table 7 ) reported side effects of their physical activity, mostly moderate ( n = 23) and easy ( n = 22), but also one ( n = 1) severe. Information about physical activity was obtained from healthcare providers (39%, n = 158), friends and family (25%, n = 100) or from the Internet or the media (24%,n = 96). Only 3% ( n = 12) received information about physical activity from alternative medicine providers. 25% ( n = 100) neither received nor asked for information about physical activities (Table 4 ). Most participants (67%, n = 271) discussed their physical activities with healthcare providers, mostly their family doctor (42%, n = 167), oncologists (29%, n = 118) or with a nurse (15%, n = 60), but also with other healthcare providers (17%, n = 70). Non discussed their physical activities with alternative medicine providers (Table 4).

Spiritual practices

A third of the participants (30%, n = 132) reported participating in spiritual practices, 40% ( n = 53) of which in more than one practice with a mean of 1.5 different spiritual practices (range 1-4). The prayer was the most practiced. They prayed themselves (20%, n = 85) or were prayed for by others (20%, n = 85). The majority prayed to increase quality of life, to cope, to relax, to increase well-being (45%, n = 59) or for other reasons (42%, n = 56). Two individuals experienced adverse effects from spiritual practices (prayer), one moderate and one mild (Table 7). Total 29% ( n = 37) reported improvements from these spiritual practices, while 45% ( n = 58) reported no change (Table 4 ). Most often, they did not seek or receive information about their spiritual practices (44%, n = 58), but 30% ( n = 39) received information from family or friends. Some also sought information from other sources (21%, n = 28). The spiritual practices were predominantly not discussed with healthcare providers (89%, n = 117, Table 4 ).

Use of alternative medicine according to the NAFCAM alternative medicine reporting model

When reported alternative medicine use was adjusted to the NAFCAM alternative medicine reporting model, we found that 33% ( n = 143) reported alternative medicine at level 2, 79% at levels 3 and 4 ( n = 346 or 347), 96% ( n = 421) at level 5 and 97% ( n = 424) at level 6. Alternative medicine was used more often by women than men at alternative medicine levels 2–4. No gender differences were found for alternative medicine levels 5 and 6 (Table 8 ).

| Reason(s) for use (multiple selection) | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| In total | Women | Men | p -Value* | To treat cancer or prevent it from spreading | To treat side effects or long-term effects of cancer/cancer treatments | To strengthen the body/immune system | To increase quality of life, coping, relaxation or well-being | Other reasons | Side effects | ||

| % (n) | % (n) | % (n) | % (n) | % (n) | % (n) | % (n) | % (n) | % (n) | % (n) | ||

| Alternative medicine level 2 | 32.8 (143) | 38.9 (114) | 20.3 (29) | <0.001 | 7 (10) | 59.4 (85) | 30.1 (43) | 63.6 (91) | 9.1 (13) | 7.7 (11) |  |

| Alternative medicine level 3 | 78.8 (346) | 83.1 (246) | 69.9 (100) | 0.002 | 15.9 (55) | 48.0 (166) | 73.1 (253) | 79.2 (274) | 13.6 (47) | 9.0 (31) | |

| Alternative medicine level 4 | 79.0 (347) | 83.1 (246) | 70.6 (101) | 0.003 | 16.4 (57) | 48.1 (167) | 73.2 (254) | 79.3 (275) | 13.5 (47) | 9.8 (34) | |

| Alternative medicine level 5 | 96.1 (421) | 96.6 (285) | 95.1 (136) | 0.444 | 16.9 (71) | 55.8 (235) | 82.7 (348) | 93.8 (395) | 16.2 (68) | 15.2 (64) | |

| Alternative medicine level 6 | 96.8 (424) | 96.9 (286) | 96.5 (138) | 0.804 | 23.6 (100) | 56.6 (240) | 82.3 (349) | 93.6 (397) | 25.7 (109) | 15.1 (64) | |

*Pearson chi-square test; Alternative Medicine Level 2: One or more visits to alternative medicine providers; Alternative Medicine Level 3: Alternative Medicine Level 2 and/or use of natural remedies and self-help practices; Alternative Medicine Level 4: Alternative Medicine Level 3 and/or special diets; Alternative Medicine Level 5: Alternative Medicine Level 4 and/or physical activity; Alternative Medicine Level 6: Alternative Medicine Level 5 and/or use of spiritual practices

The most common reason for using alternative medicine was to improve quality of life for all levels of alternative medicine (79% – 94%). The highest use of alternative medicine to treat the cancer or prevent its spread was found at level 6, where spiritual practices were added (Tables 7 and 8). Adverse events were low at all levels (8%–15%), highest at level 5, where physical activity was added to visits to alternative medicine providers, use of natural remedies, self-help practices, and special diets (Table 7 ).

discussion

Main results

A large proportion of cancer patients included in this survey (79%) had used alternative medicine (Level 3); 33% had seen alternative medicine providers, 52% had used natural remedies, while 58% had used self-help practices. The cancer patients used the various alternative medicine modalities primarily to increase quality of life, to cope with cancer or for relaxation/well-being (64%–94%). Participants reported high satisfaction with visits to alternative medicine providers and self-care practices in terms of improvement in symptoms (87% and 81%, respectively). but not to the same extent for the use of natural remedies (35%). Few reported side effects from their alternative medicine treatments (9%). Many users had multiple reasons/motives for using an alternative medicine modality. For information about alternative medicine modalities, participants most often searched online for natural remedies (45%), while consulting health care providers for information about provider-based alternative medicine therapies (43%) and self-care practices (38%). A total of 41% did not discuss their use of alternative medicine with a doctor.

Agreements and disagreements with other studies

The prevalence of alternative medicine use at level 3 (alternative medicine providers, natural remedies and/or self-help practices) among Norwegian cancer patients found in this study was higher than previously found among cancer patients in Scandinavia in general (36%)(link removed)and in several Nordic studies(link removed). A Swedish study found that 26% of cancer patients used alternative medicine at level 4(link removed)after the cancer diagnosis. A Danish study of breast cancer patients reported 50% use of alternative medicine(link removed), while a Danish study reported 49% in colorectal cancer patients, both at stage 3(link removed).. A previous Norwegian study in cancer patients found 33% use of alternative medicine at level 3, all three studies (the two Danish and the previous Norwegian study) within a 12-month time frame(link removed). It was also higher than studies from Europe (30%)(link removed), North America (46%), Australia/New Zealand (40%)(link removed)and was found in a recent global systematic review (51%). (link removed). One reason for this discrepancy in prevalence could be the large number of alternative medicine modalities reported in our study. The modalities provided served as a reminder to participants and informed them about how to define alternative medicine. The alternative medicine use reported in our study is consistent with results from other studies using similarly specified questionnaires, such as . Breast cancer patients are known to use alternative medicine more frequently than patients with other cancer diagnoses(link removed).. This factor may also contribute to the high prevalence of alternative medicine use in our study, as 39% of participants suffered from breast cancer. The high percentage of middle-aged, college-educated women in the study may also have contributed to the high number of participants who reported using alternative medicine, as both female gender, higher education, and young to middle age predict alternative medicine use. The time since diagnosis category may also influence the high prevalence of use in our study, as we included responses from participants who had been diagnosed with cancer many years ago. Several of the above studies reported use of alternative medicine within a 12-month period or during cancer treatment, while we asked about use since cancer diagnosis.

The fact that the study was conducted 1½ years after the start of the COVID-19 pandemic may also have influenced the results, as people appear to be using alternative medicine more during the pandemic than before, particularly self-administered modalities such as self-help techniques and natural remedies(link removed). This is consistent with this present study, in which self-administered modalities were most commonly used. The high use of self-administered modalities is consistent with findings from other studies(link removed), where natural remedies were widely used(link removed).. The most commonly used self-administered modality in the present study was relaxation therapy (49%), reflecting the reported primary reasons for general alternative medicine use to increase quality of life, cope, relax and improve well-being. These reasons for using alternative medicine are consistent with the results of the Swedish study(link removed), where the main reason for using alternative medicine was to increase well-being. According to research(link removed)Stress can negatively impact cancer patients and their immune response, potentially affecting the development and progression of the disease. Relaxation therapies have been shown to be beneficial in reducing stress in cancer patients(link removed).

The second most commonly used alternative medicine modality in this study was omega-3, 6, or 9 fatty acids (31%). The connection between omega-3, 6, or 9 fatty acids and cancer risk is unclear(link removed).. We found; However, the participants used these fatty acids (91%) to strengthen the body and immune system. Only 8% used it to treat the cancer or prevent it from spreading. 26 percent used it to improve their quality of life. This was particularly true for participants who suffered from depression and anxiety as a result of their cancer. Depression affects the quality of life of approximately 20% of cancer patients and antidepressants, along with various psychotherapeutic interventions, are the best established treatment for depression in cancer. Many patients experience; Side effects of antidepressants(link removed)while at the same time restricting access to psychotherapeutic interventions(link removed).. Therefore, an accessible intervention with fewer side effects is needed for the treatment of depression in cancer patients. Psychiatric studies have examined the association between depression and omega-3 fatty acid as a possible complementary and well-tolerated intervention for cancer patients suffering from depression(link removed). Several meta-analyses have reported positive results for omega-3 fatty acids in the treatment of depression(link removed), although a Cochrane review concluded that the overall results are not unanimously positive(link removed).

Although the majority of users do not use natural remedies with the intent to treat or prevent cancer, it is interesting to note that the use of some of these specific remedies (e.g., omega-3, 6, 9, ginger, green tea, and garlic) are used remarkably more frequently than recently reported by our research group in a general population-based study using the I-CAM-Q questionnaire was reported(link removed). This higher use among people with cancer or with a history of cancer compared to the general population confirms the special need for good information and communication strategies of alternative medicine in the context of cancer treatment(link removed).

The most commonly used modalities to treat cancer/prevent its spread were turmeric/curcumin (n = 20), ginger (n = 13), and green tea (n = 13). The minority of participants; however, used these modalities, resulting in an overall use of alternative medicine (level 3) of 16% (n = 55) to treat the cancer or prevent its spread. This is slightly less than what was found in a recent systematic review, which found treating or curing cancer as the most common reason for using alternative medicine. One reason for this discrepancy could be the legal situation in Norway, where alternative medicine providers are not allowed to treat the cancer unless this is done in consultation with the patient's doctor or there is no curative or palliative treatment available for the patient(link removed). Otherwise, alternative medicine providers are only permitted to provide treatment that aims to manage the consequences of illness or treatment-related side effects or to strengthen the body's immune system and its self-healing powers(link removed).

Our finding that female cancer patients use more alternative medicine at levels 2-4 is consistent with the majority of other studies, both nationally(link removed)as well as internationally(link removed). Women generally use health services more frequently than men(link removed), however, report that they have more unmet health care needs within conventional health care than men(link removed). This could be the reason why women choose alternative medicine at a higher rate than men(link removed).

information

In contrast to previous findings, which show that alternative medicine users primarily obtain information about alternative medicine modalities on the Internet, in the media and among friends and family(link removed); Half of alternative medicine users (at level 3) in the present study obtain information about alternative medicine from healthcare providers, the Internet and media (47%), and family and friends (39%). These results confirm previous studies reporting that patients prefer to receive information about alternative medicine from their healthcare providers(link removed). The results are also consistent with previous findings showing that 50% of doctors and 57% of nurses seek evidence-based information about alternative medicine in cancer care(link removed), presumably to pass them on to patients. The information may have been provided to the patient upon request when discussing their alternative medicine use and was not necessarily offered routinely. Cancer patients need information about safety and effectiveness from trusted sources and would welcome a hospital-based alternative medicine training program(link removed). The majority of doctors (89%) and nurses (88%) in cancer care in Norway say they are moderately or very satisfied with answering questions about alternative medicine(link removed). In addition to recognizing the reported need for information, NAFCAM has also addressed the issue by publishing a specialist database of evidence-based information on alternative medicine for cancer for healthcare providers in English(link removed)as well as patient versions on its website in Norwegian(link removed)concerned.62. In addition, NAFCAM and the NCS conducted 16 public topic meetings across the country and a digital toolbox for healthcare providers on alternative medicine was created(link removed).

communication

Despite the fact that only 31% of Norwegian cancer doctors regularly ask their patients about their use of alternative medicine(link removed), more than half of alternative medicine users (59%, Level 3) in this study discussed one or more of the following modalities they used with a doctor, either their primary care physician (49%) or their oncologist (36%). This is consistent with a systematic review reporting secrecy rates of 20-77% with an average of 40-50% based on 21 international studies(link removed)and a previous Norwegian study of cancer patients receiving chemotherapy, which reported non-disclosure rates of 28-54%(link removed). While the disclosure rate in the present Norwegian study was in good agreement with internationally reported studies, the disclosure rate was higher than in studies conducted in other Scandinavian countries(link removed), but lower than in an American study of breast cancer patients (disclosure rates of 71-85%)(link removed). Reasons for disclosing or not disclosing alternative medicine use can be varied.

The higher Disclosure rate in the present study compared to a Swedish study (disclosure rate of 33%)(link removed)and a Danish study of colorectal cancer patients (disclosure rate of 49%) could be due to the slightly higher proportion of female doctors in Norway (54%)(link removed)compared to Sweden (44%)(link removed)and Denmark (51%)(link removed), as it has been reported that female doctors are more likely to talk about using alternative medicine with their patients than their male colleagues(link removed). In general, female doctors seem to offer more patient-centered advice to patients(link removed)and spend more time with their patients(link removed), which gives patients more time to address the issue themselves. Although gender equality is high in all Scandinavian countries, the proportion of female doctors is highest in Norway(link removed). Additionally, the current study asked about a wide range of alternative medicine modalities, and the majority of participants (75%) used more than one alternative medicine modality (range 1–17), with an average of 3.8 modalities each. Users may have only discussed the use of one of the modalities rather than all modalities, which may not have resulted in a broader range of alternative medicine modalities has discussed with physicians than the 59% disclosure rate suggests. Disclosure of natural remedies was particularly low, with only 30% reporting discussing such use with a doctor. This is consistent with previous findings showing that disclosure of alternative medicine use to medical providers for self-care is lower than for provider-based alternative medicine(link removed). The reason for the particularly low disclosure rate for natural remedies could be that doctors often advise against such use(link removed), because the potential risk of interactions with conventional cancer treatments is highest with these agents.

Those reported in the present study lower Disclosure rates compared to those in the US study in breast cancer patients (disclosure rates of 71-85%)(link removed)could be due to women generally being more likely to disclose their use of alternative medicine(link removed)and differences in consultation practices between Norway and the USA. While integrative oncology is more widespread in the United States, where evidence-based integrative oncology guidelines are also available(link removed), it is rarely practiced in Norway(link removed). Patients in Norway therefore tend to pursue alternative medicine and conventional care in parallel(link removed). This may have contributed to a counseling practice in which communication about the patient's use of alternative medicine does not have a natural place, resulting in lower disclosure rates compared to those reported in the US study(link removed).

Many patients do not disclose their alternative medicine use because they are not asked or believe it has no relevance to medical providers(link removed), while others fear being stigmatized if they disclose their alternative medicine use(link removed). , 82, 83. Disclosure is influenced by the nature of patient-physician communication and beliefs in supporting alternative medicine use(link removed). In some countries the legal situation may also have an influence. In Norway, as mentioned above, alternative medicine providers are only allowed to treat cancer patients for the sole purpose of managing side effects of cancer and cancer treatment or supporting the immune system and the body's ability to heal itself, unless the treatment is carried out in collaboration with the patient's doctor, which is rare(link removed). This may have resulted in the provider-based alternative medicine treatment not being disclosed. This is not; However, this is true for the majority of participants, as only 7% reported provider-based alternative medicine treatment aimed at treating cancer and preventing its spread.

Given the high prevalence of alternative medicine use and low disclosure rates, it is of paramount importance to promote patient health literacy. Oncology providers cite a lack of knowledge as the most common reason for not asking patients about their use of alternative medicine(link removed). To increase disclosure rates and improve the quality of communication about alternative medicine, a recent review and clinical practice guidelines proposed seven clinical practice recommendations(link removed).

Strengths and limitations of the study

The main strengths of the study are the fairly high response rate, the adequate study power, the wide range of cancer locations and diagnoses, an age distribution similar to that of adult cancer survivors in Norway, and the geographical distribution of participants representing all parts of Norway. rural and urban. This study was not conducted in a hospital setting and therefore is not limited to patients currently receiving conventional cancer treatment. The study must; however, should be understood in light of some limitations. The main limitation of the study is that the NCS user panel members do not fully represent the entire cancer population in Norway. For example, in terms of gender, there were more female participants in the survey than female cancer patients in general (67% vs. 46%). This bias was resolved by partially presenting gender-specific data. Another limitation was that all groups had an “other therapies” option without asking for information. These options were excluded from the analyzes because we could not determine whether they were alternative medicine or not. On the other hand, this contributed to a possible under-reporting of alternative medicine users.

Implication of the results

The high use of alternative medicine among Norwegian cancer patients has several implications. First, healthcare providers should routinely ask cancer patients about their alternative medicine use. Many patients use herbs and other natural remedies, but these can interact with traditional cancer treatment. Ginger (used by 20%), green tea (used by 17%), and turmeric/curcumin (used by 11%) are examples of herbs that may influence cancer and cancer treatment(link removed). The risk of adverse interactions increases when patients do not discuss such use with their oncologist, which only 17% of natural medicine users in this study did.

Second, given that many alternative medicine products are available over the counter or over the Internet and many patients choose self-care practices, there is also a particular need for improved health literacy among cancer patients. It is important that patients understand health-related information and can make informed decisions about their health, including discussions with their cancer doctors. NAFCAM and NCS have worked closely to provide such information to cancer patients by organizing information workshops with regional cancer groups, publishing patient information, and general tools for understanding safety issues(link removed)and will implement this new knowledge in future patient information.

Third, the findings from this study will inform the teaching of healthcare providers and students, as well as informing patients and families through various channels. The results could also be relevant for advocacy work, for example through advisory contributions and the strategy for increasing health literacy in the population(link removed).

Finally, oncologists should also respond to patients' unmet needs for supportive alternative medicine treatment to improve quality of life and well-being, as well as their desire to actively contribute to treatment. The high satisfaction reported in this study with several alternative medicine modalities to improve quality of life could be used to improve patient information about such modalities, as previous studies have shown that patients value such information and prefer to receive it from health care providers(link removed).

Conclusion

Four out of five participants in this study used alternative medicine with high levels of satisfaction and low rates of side effects. The main reasons for using alternative medicine were: Increasing quality of life, coping, relaxation or well-being, followed by strengthening the body and immune system . Given the high prevalence figures, providing reliable information that supports healthcare providers' knowledge and patients' health literacy, as well as communicating the benefits and harms of such treatments, is crucial. The collaboration between NCS and NAFCAM is an example of how these issues can be addressed.

Availability of data and materials

The data set on which this work is based has not been deposited in any repository. All datasets and materials are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request. However, applicants for data must be prepared to comply with Norwegian data protection regulations.

References

-

Cancer in Norway 2020

-

Complementary and alternative medicine (link removed)

-

Love dates. Law No. 64 of June 27, 2003 on the alternative treatment of illness, disease, etc. (link removed) .

-

Kristoffersen AE, Fonnebo V, Norheim AJ. Use of complementary and alternative medicine by patients: Classification criteria determine use. J Altern Complement Med. 2008;14(8):911–9.

-

Kristoffersen AE, Quandt SA, Stub T. Use of complementary and alternative medicine in Norway: a cross-sectional survey using a modified Norwegian version of the international questionnaire for measuring the use of complementary and alternative medicine (I-CAM-QN). BMC complementary medicine and therapies. 2021;21(1):1–12.

-

Risberg T, Lund E, Wist E, Kaasa S, Wilsgaard T. Use of an unproven therapy in cancer patients: a 5-year follow-up study. J Clin Oncol. 1998;16(1):6–12.

-

Kristoffersen AE, Stub T, Broderstad AR, Hansen AH. Use of traditional and complementary medicine among Norwegian cancer patients in the seventh survey of the Tromso Study. BMC Supplement Altern Med. 2019;19(1):341.

-

Wode K, Henriksson R, Sharp L, Stoltenberg A, Hok Nordberg J. Use of complementary and alternative medicine among cancer patients in Sweden: a cross-sectional study. BMC Supplement Altern Med. 2019;19(1):62.

-

Horneber M, Bueschel G, Dennert G, Less D, Ritter E, Zwahlen M. How many cancer patients use complementary and alternative medicine: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Integr. Cancer Ther. 2012;11(3):187–203.

-

Keene MR, Heslop IM, Sabesan SS, Glass BD. Application of complementary and alternative medicine in cancer: A systematic review. Complete Ther Clin Pract. 2019;35:33–47.

-

T Risberg, A Vickers, RM Bremnes, EA Wist, S Kaasa, BR Cassileth. Does the use of alternative medicine predict cancer survival? Your J Krebs. 2003;39(3):372–7.

-

Molassiotis A, Fernadez-Ortega P, Pud D, Ozden G, Scott JA, Panteli V, Margulies A, Browall M, Magri M, Selvekerova S, et al. Use of complementary and alternative medicine in cancer patients: a European survey. Ann Oncol. 2005;16(4):655–63.

-

Langas-Larsen A, Salamonsen A, Kristoffersen AE, Hamran T, Evjen B, Stub T. “We own the disease”: a qualitative study of networks in two mixed-ethnicity communities in Northern Norway. Int J Circumpolar Health. 2018;77(1):1438572.

-

Kemppainen LM, Kemppainen TT, Reippainen JA, Salmenniemi ST, Vuolanto PH. Use of complementary and alternative medicine in Europe: Health-related and sociodemographic determinants. Scand J Public Health. 2018;46(4):448–55.

-

Nakandi KS, Mora D, Stub T, Kristoffersen AE. Traditional health service utilization among cancer survivors attending traditional and complementary providers in the Tromsø study: A cross-sectional study. BMC Health Serv Res. 2022;22(11):53.

-

Jacobsen R, Fonnebo VM, Foss N, Kristoffersen AE. Use of complementary and alternative medicine in Norwegian hospitals. BMC Supplement Altern Med. 2015;15:275.

-

T. Risberg, A. Kolstad, Y. Bremnes, H. Holte, EA Wist, O. Mella, O. Klepp, T. Wilsgaard, BR. Cassileth. Knowledge and attitudes towards complementary and alternative therapies; a national multicenter study of oncologists in Norway. Your J Krebs. 2004;40(4):529–35.

-

Stub T, Quandt SA, Arcury TA, Sandberg JC, Kristoffersen AE. Attitudes and knowledge about direct and indirect risks among conventional and complementary healthcare providers in cancer treatment. BMC Supplement Altern Med. 2018;18(1):44.

-

Kolstad A, Risberg T, Bremnes Y, Wilsgaard T, Holte H, Klepp O, Mella O, Wist E. Use of complementary and alternative therapies: a national multicenter study of oncology health professionals in Norway. Support Care Cancer. 2004;12(5):312–8.

-

T Stub, SA Quandt, TA Arcury, JC Sandberg, AE Kristoffersen, F Musial, A Salamonsen. BMC Supplement Altern Med. 2016;16(1):1–14.

-

Salamonsen A. Doctor-patient communication and the choice of alternative therapies by cancer patients as a supplement or alternative to conventional care. Scand J Caring Sci. 2013;27(1):70–6.

-

Krogstad T, Nguyen M, Widing E, Toverud EL. Bruk av naturpreparater and kosttilskudd hos kreftsyke barn in Norge. Tidssr Nor Lægeforen. 2007;19(127):2524–6.

-

Stub T, Quandt SA, Arcury TA, Sandberg JC, Kristoffersen AE. Complementary and conventional providers in cancer care: Experience in communicating with patients and steps to improve communication with other providers. BMC Supplement Altern Med. 2017;17(1):301.

-

Tovey P, Broom A. Oncologists' and specialist cancer nurses' approaches to complementary and alternative medicine and their impact on patient behavior. Soc Sci Med 2007;64:2550–64.

-

Quandt SA, Verhoef MJ, Arcury TA, Lewith GT, Steinsbekk A, Kristoffersen AE, Wahner-Roedler DL, Fonnebo V. Development of an international questionnaire to measure the use of complementary and alternative medicine (I-CAM-Q). J Altern Komplement Med. 2009;15(4):331–9.

-

Sample size calculator (link removed)

-

Budwig diet https://cam-cancer.org/de/budwig-diät

-

Nilsson J, Kallman M, Ostlund U, Holgersson G, Bergqvist M, Bergstrom S. The Use of Complementary and Alternative Medicine in Scandinavia. Anti-cancer res. 2016;36(7):3243–51.

-

Pedersen CG, Christensen S, Jensen AB, Zachariae R. We trust in God and alternative medicine. Religious belief and use of complementary and alternative medicine (alternative medicine) in a nationwide cohort of women treated for early breast cancer. Journal of Religion and Health. 2013;52(3):991–1013.

-

Nissen N, Lunde A, Pedersen CG, Johannessen H. The use of complementary and alternative medicine after completion of hospital treatment for colorectal cancer: results of a questionnaire study in Denmark. BMC Supplement Aging Med 2014;14:388.

-

On ML, Schmidt S, Guthlin C. Translation and adaptation of an international questionnaire to measure the use of complementary and alternative medicine (I-Alternativmedizin-G). BMC Supplement Aging Med 2012;12:259.

-

Lengacher CA, Bennett MP, Kip KE, Gonzalez L, Jacobsen P, Cox CE. Alleviation of symptoms, side effects and psychological stress through the use of complementary and alternative medicine in women with breast cancer. Oncol Nur's Forum. 2006;33(1):1–9.

-

Kristoffersen AE, Jong M, Nordberg JH, Van der Werf E, Stub T. Safety and use of complementary and alternative medicine in Norway during the first wave of the COVID-19 pandemic using an adapted version of the I-CAM-Q: A cross-sectional survey. BMC Complement Med. Ther. In print.

-

Engdal S, Steinsbekk A, Klepp O, Nilsen OG. Use of herbs in cancer patients during palliative or curative chemotherapy in Norway. Support Care Cancer. 2008;16(7):763–9.

-

Abrahão CA, Bomfim E, Lopes-Júnior LC, Pereira-da-Silva G. Complementary therapies as a strategy to reduce stress and stimulate immunity in women with breast cancer. Journal of Evidence-Based Integrative Medicine. 2019;24:2515690X19834169.

-

Rose DP, Connolly JM. Omega-3 fatty acids as chemopreventive agents against cancer. Pharmacol. Ther. 1999;83(3):217–44.

-

Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale (HADS)

-

Suzuki S, Akechi T, Kobayashi M, Taniguchi K, Goto K, Sasaki S, Tsugane S, Nishiwaki Y, Miyaoka H, Uchitomi Y. Daily omega-3 fatty acid intake and depression in Japanese patients with newly diagnosed lung cancer. Br J Cancer. 2004;90(4):787–93.

-