Eat less for a longer life: Why an extensive study on mice provides crucial insights

A comprehensive study shows that reduced calorie intake in mice affects not only weight but also lifespan. Discover the complex connections between nutrition, immunity and longevity.

Eat less for a longer life: Why an extensive study on mice provides crucial insights

Reducing calorie intake can lead to a slimmer body – and to a longer life. This effect is often attributed to weight loss and Metabolic changes caused by less food intake, attributed. One of the largest studies 1 on dietary restriction ever performed on laboratory animals now challenges conventional wisdom about how dietary restriction increases lifespan.

In the study, which involved nearly 1,000 mice that were either fed low-calorie diets or had regular periods of fasting It was found that such programs actually cause weight loss and associated metabolic changes. But other factors – including Immune health, genetics and physiological indicators of resilience – appear to better explain how reducing calories is linked to increased lifespan.

“The metabolic changes are important,” says Gary Churchill, a mouse geneticist at the Jackson Laboratory in Bar Harbor, Maine, who co-led the study. “But they do not lead to an extension of lifespan.”

To outsiders, the results underscore the complex and individual nature of the body's response to calorie-restricted diets. “It reveals the complexity of this intervention,” says James Nelson, a biogerontologist at the University of Texas Health Science Center at San Antonio.

The study was published today in the journal Nature by Churchill and his co-authors, including scientists from Calico Life Sciences in South San Francisco, California, the anti-aging biotech company that funded the study.

Count calories

Scientists have long known that calorie-reducing measures, i.e. long-term restrictions on food intake, extend the lifespan of laboratory animals. Some studies have shown that intermittent fasting, which involves short periods of food deprivation, can also increase longevity.

To learn more about how such diets work, researchers monitored the health and lifespan of 960 mice, each of which represented genetically distinct examples of a diverse population that reflects human genetic variability. Some mice were placed on calorie-restricted diets, another group followed intermittent fasting regimes, and others were allowed to eat freely.

Reducing calorie intake by 40 percent resulted in the greatest increase in lifespan, but intermittent fasting and less strict calorie restrictions also increased average lifespan. The dieted mice also showed favorable metabolic changes, such as a reduction in body fat percentage and blood sugar levels.

However, the effects of dietary restriction on metabolism and lifespan did not always change synchronously. One of the authors' surprises was that the mice that lost the most weight on a calorie-limiting diet tended to die earlier than animals that lost relatively moderate amounts.

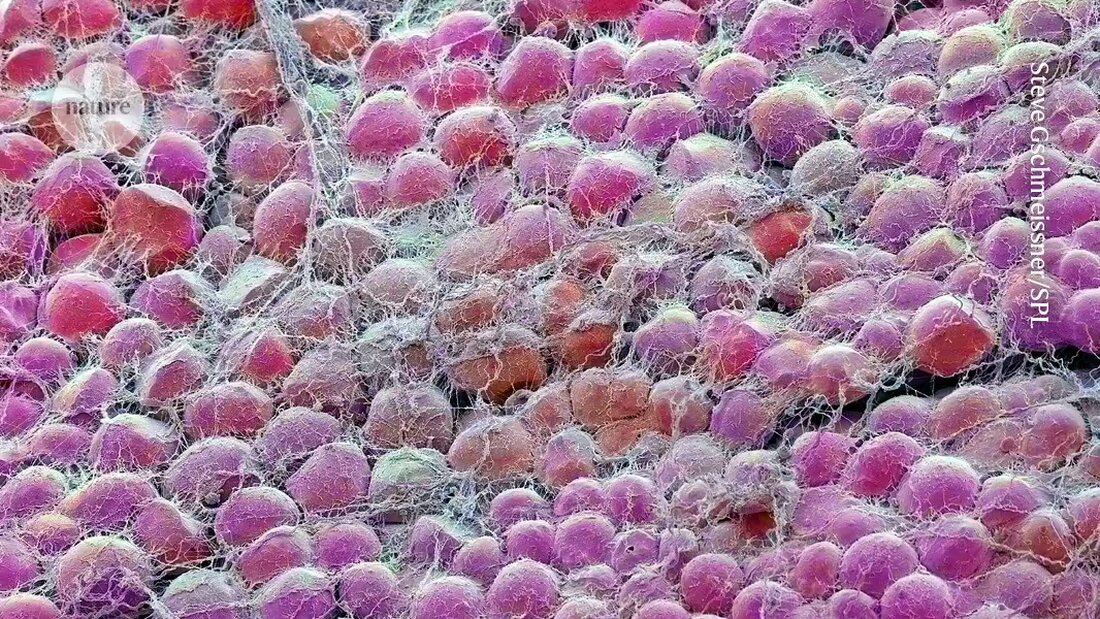

This suggests that processes beyond simple metabolic regulation determine how the body responds to calorie-restricted diets. The most important factors in extending lifespan were traits related to immune health and red blood cell function. Also crucial was the general resilience, which is probably encoded in the animals' genes, to the stress of reduced food intake.

“The intervention is a stressor,” explains Churchill. The most resilient animals lost the least weight, maintained their immune function and lived longer.

Slimness for longevity

The findings could change the way scientists view studies of dietary restrictions in humans. In one of the most comprehensive clinical studies 2 to a low-calorie diet in healthy, non-obese people, researchers found that the intervention helped slow down metabolism – a short-term effect that is considered to be indicative of long-term lifespan benefits.

However, Churchill's team's mouse data suggests that metabolic measurements may reflect 'healthspan' - the period of time spent living free from chronic disease and disability - but that further metrics are needed to determine whether such 'anti-aging' strategies can actually extend life.

Daniel Belsky, an epidemiologist who studies aging at the Columbia University Mailman School of Public Health in New York City, cautions against generalizing from mice to humans. But he also acknowledges that the study "contributes to the growing understanding that duration of health and lifespan are not the same thing."

-

Di Francesco, A. et al. Nature https://doi.org/10.1038/s41586-024-08026-3 (2024).

-

Redman, L.M. et al. Cell Metab. 27, 805–815 (2018).

Suche

Suche

Mein Konto

Mein Konto