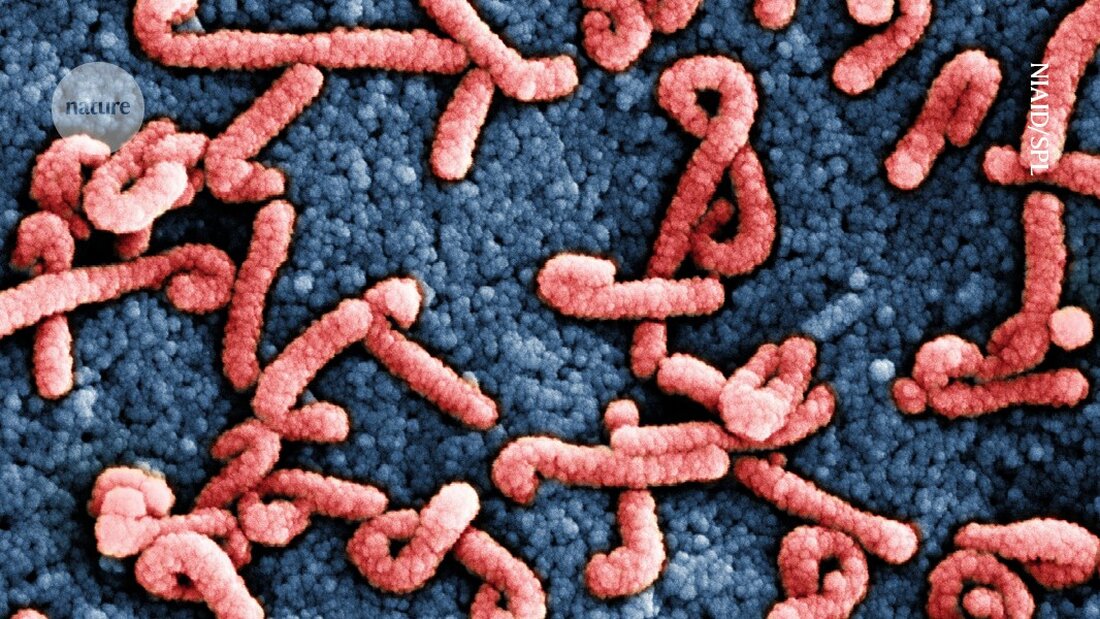

Viruses jumping from animals to humans trigger deadly Marburg outbreak

A single virus jump from animals to humans triggered a deadly Marburg outbreak in Rwanda, which counts 63 infected people and 15 deaths.

Viruses jumping from animals to humans trigger deadly Marburg outbreak

The third largest eruption in the history of the deadly Marburg virus was through a single jump of the pathogen from animals to humans initial genomic evidence shows.

The outbreak began last month in Rwanda, where 63 people have been infected, 15 of whom have died. Further evidence suggests that the first person to become infected in the outbreak likely became ill during a visit to a cave that houses a species of bat that carries the virus.

Multiple transmissions from animals to humans have raised fears that the virus is more widespread in Rwanda than previously thought. In addition, an unclear origin of the virus could have increased the prospect of new outbreaks.

Rwanda's response to the virus also helped contain the outbreak, researchers report. Scientists praise the country's efforts to control the outbreak, investigate its origins and share data with the scientific community. “As soon as they realized there was a problem, they initiated contact tracing, conducted a thorough epidemiological investigation, identified the [first] patient and possibly found the source of infection — and within a week one Test trial with an experimental vaccine started," says Angela Rasmussen, a virologist at the University of Saskatchewan in Saskatoon, Canada. This shows that with Marburg virus disease, "a rapid and urgent response can mitigate the severity of the outbreak," she adds.

The findings, which have not yet been published in full or peer-reviewed, were published on the social platform X and discussed during a media event on October 20th.

Rapid containment

The outbreak, declared on September 27, is Rwanda's first; Tanzania and Equatorial Guinea recorded their first Marburg outbreaks last year, and Ghane had its first in 2022. Marburg outbreaks — which cause high fever, severe diarrhea, nausea and vomiting, and in severe cases lead to bleeding from the nose or gums — currently occur about once a year, whereas before the 2020s they were mostly detected only a few times a decade.

Since the outbreak began, reports of new infections have declined significantly. Rwandan health officials have recorded one new case and no deaths in the past 10 days, and only two people remain in isolation and treatment. A Marburg outbreak can be declared over when no new cases have been reported for 42 consecutive days.

There is no proven vaccine or treatment for infections with the virus closely related to the Ebola virus is, both in its symptoms and in its transmission, which occurs primarily through contact with body fluids. Health officials are offering a candidate vaccine, made by the Sabin Vaccine Institute in Washington DC, to contacts of infected people. More than 1,200 doses have been administered so far.

This outbreak has one of the lowest mortality rates — about 24% — for Marburg ever recorded; previous outbreaks reported mortality rates as high as 90%. This is likely the result of rapid diagnoses, access to medical care and the fact that most infections occurred among relatively young healthcare workers.

In fact, two people infected with the virus and supported on life support were successfully intubated and later extubated while they recovered. This marks the first time that people with Marburg virus disease have been extubated in Africa, said Tedros Adhanom Ghebreyesus, director general of the World Health Organization in Geneva, Switzerland, during a news conference on October 20. “These patients would have died in previous outbreaks,” he added.

Single origin

To help contain the outbreak, researchers at the Rwanda Biomedical Center in Kigali the genome of the Marburg virus sequenced from several infected individuals. They found that all the samples were very similar to each other, suggesting that the virus spread quickly in a short period of time and that they had a common origin. They also discovered that the virus strain is closely related to one detected in Uganda in 2014 and one found in bats in 2009, said Yvan Butera, Rwanda's minister of state for health, who co-led the research.

A comparison of the 2014 strain with the one causing the current outbreak shows a "limited mutation rate," Butera says, suggesting there have likely been few changes in the virus's transmissibility or lethality over the past decade. In general, viruses accumulate mutations as they reproduce over time; If it is true that the mutation rate is low, Rasmussen wonders how the virus survives in its animal reservoir - the Egyptian fruit bat (Rousettus aegyptiacus) — can remain without significant changes.

Researchers point out that Environmental threats such as climate change and deforestation have increased the likelihood of humans encountering animals that can transmit infections. More data on how the virus persists in bats — as well as in which tissues — could help sensitize surveillance efforts, giving health authorities a better picture of virus hotspots, Rasmussen adds.

Butera explains that the genomic analyzes are being completed; he and his colleagues hope to share the full data by the end of the week.

Suche

Suche

Mein Konto

Mein Konto