Plant Scientist will decide whether to rid their discipline of offensive names.

This week, the group that sets the rules for naming plant species will vote on whether to rename dozens of organisms whose scientific names contain a racist term, as well as whether to reconsider other offensive names, such as those that recognize colonial rulers or people who supported slavery.

The votes at the International Botanical Congress in Madrid mark the first time that taxonomists have officially considered rule changes to deal with species names that are offensive to many people.

Proponents of the proposals argue that academia, like broader society, should address the veneration of people who have committed historical injustices. However, some in the taxonomic world fear that a mass renaming could cause confusion in the scientific literature and create a 'steep road' that could jeopardize any species name recognition by a human.

“It's very unfortunate that many of these names are offensive,” says Alina Freire-Fierro, a botanist at the Cotopaxi Technical University in Latacunga, Ecuador. “Changing the names that have already been released would cause so much confusion.”

Serious names

Proponents of the changes point out that species names and taxonomy rules are constantly in flux - hundreds of proposals to change plant name rules will be discussed at this year's meeting. Eliminating particularly serious names is just a drop in the bucket compared to the changes already made when, for example, a genetic analysis splits a single species into multiple species or reveals new relationships between species, say scientists who support the measures.

“It would be great to have a mechanism to weed out some of the most offensive names,” adds Lennard Gillman, a retired evolutionary biogeographer and independent consultant in Auckland, New Zealand.

Taxonomists meet every six to seven years at a conference called the International Botanical Congress to discuss changes to the rules for naming plants as well as fungi and algae (a separate group is responsible for animal names). Later this week, members of the Nomenclature Division will vote on two proposals that address culturally sensitive names.

New plant species are usually named by the scientists who discover them, with a key requirement being that a description appear in scientific literature. In the nineteenth and even well into the twentieth century, the primarily European scientists who officially named species found in the non-Western world often acknowledged colonizers such as politician Cecil Rhodes and patrons.

One of the proposals aims to rename about 218 species whose scientific names are based on the word 'caffra' and various derivatives of it - which are ethnic slurs often used against blacks in South Africa - and replace them with derivatives of 'afr', recognizing Africa instead. The second proposal, if approved, would create a committee to review offensive and culturally inappropriate names.

Measure support

In a pre-convention vote to find out how much support there is for the hundreds of proposals, nearly 50% of voters supported changing the scientific names of plants likeErythrina caffra, commonly known as coastal coral treeErythrina affra. The proposal to create the committee narrowly passed the required threshold to be voted on in person this week.

Gideon Smith, a plant taxonomist at Nelson Mandela University (NMU) in Gqeberha, South Africa, expects an extremely close vote on the 'caffra' amendment, which he tabled with his colleague NMU taxonomist Estrela Figueiredo. To pass, the vote requires a 60% two-thirds majority, but the outcome will depend on who attends the congress as well as the 'institutional votes' that allow herbaria such as the Royal Botanic Gardens, Kew, in London to assign voting rights to a participant by proxy, says Smith.

“There is resistance to these proposals, a fear of throwing plant nomenclature into chaos,” says Smith. But he adds that the benefit of scientists no longer being forced to use a term that they find deeply offensive far outweighs the minimal practical consequences of the changes. “I can’t think of an easier way to get rid of this racist expression.”

Kevin Thiele, a plant taxonomist at the Australian National University in Canberra, expects that if his proposal to create a mechanism to eliminate offensive names is approved, only a relatively small number of species names would be changed. It's likely that the argument for stability in species names would only prevail in cases where plants are named after "sufficiently serious" individuals, he says.

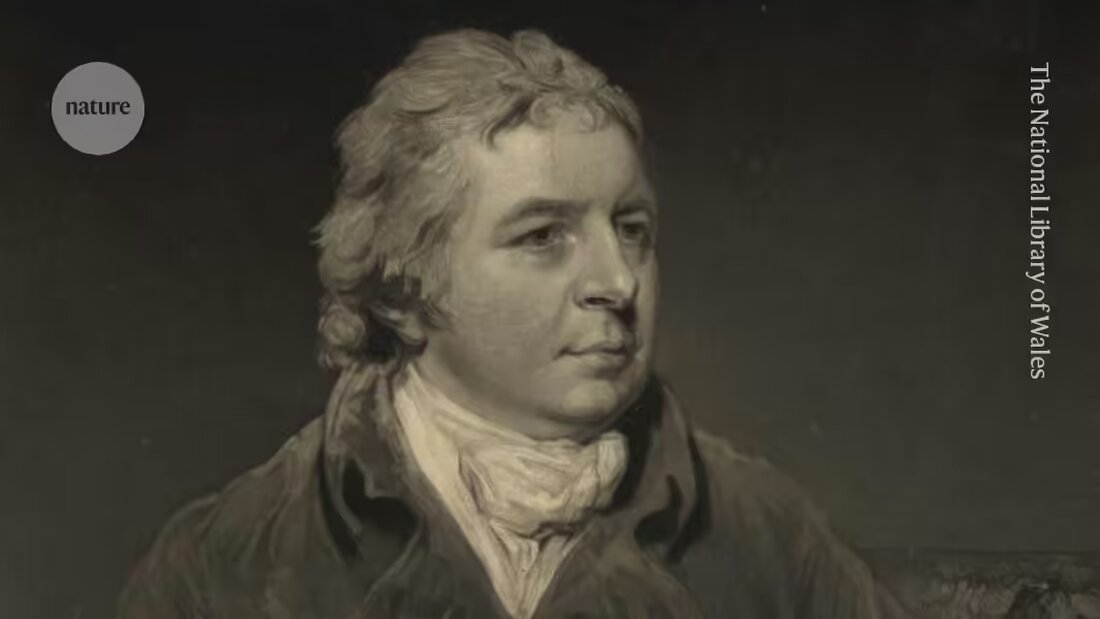

One change Thiele would like to see involves a genus of flowering shrubs, most of which have yellow flowers, found in Australia calledHibbertia, where new species are regularly discovered. They are named after George Hibbert, an eighteenth-century English merchant who profited from the slave trade and fought against abolition. “There should be a way to deal with cases like Hibbert,” he says.

Limited resources

Alexandre Antonelli, a Brazilian scientist and head of natural sciences at Kew, understands such concerns and would like to lead a broader discussion about how to increase equity, diversity and inclusion in the field. However, he worries about the practicalities and unintended consequences of changing the naming rules, such as who would judge changes or how disagreements would be resolved. Furthermore, Antonelli argues that limited resources should be better focused on cataloging, studying and protecting biodiversity. “I would not support proposals that hinder this process,” he says.

Some researchers have even called for major changes: a End the practice of naming species after people 1. But that doesn't seem fair, says Freire-Fierro, and could deprive researchers in the global south of the opportunity to name species they discover after local scientists and indigenous leaders or to raise money for conservation.

Even if the two proposals under consideration don't pass, Thiele and others say the problems they're trying to solve won't go away. For example, Gillman would like to see future botanical conventions replace some existing plant names with names long used by indigenous groups. “It would be very cool if they get something passed this week,” he said of the vote. “Change often happens gradually.”

Suche

Suche

Mein Konto

Mein Konto