Artificial intelligence (AI) is helping to redraw the family tree of viruses. Predicted protein structures using AlphaFold and chatbot-inspired ones “Protein language models” have uncovered surprising connections in a family of viruses that includes pathogens that infect humans and emerging threats.

A large part of scientists' understanding about viral evolution is based on comparing genomes. However, the lightning-fast evolution of viruses, particularly those with RNA genomes, and their propensity to acquire genetic material from other organisms shows that genetic sequences can hide deeper and more distant relationships between viruses, which can vary depending on the gene being studied.

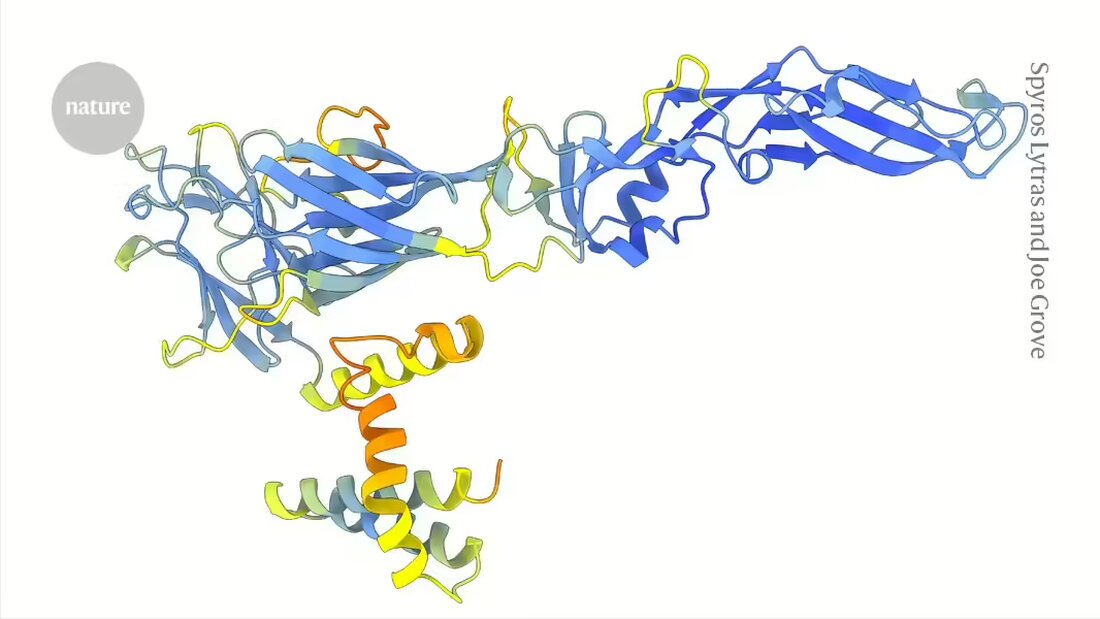

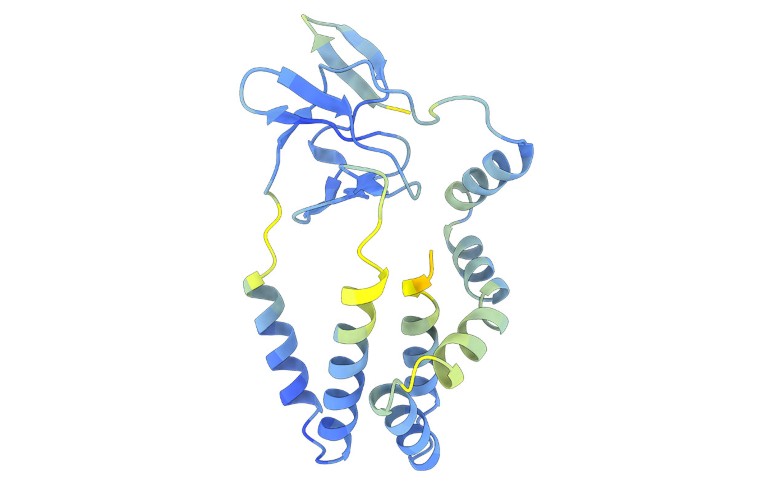

In contrast, the shapes or structures of the proteins encoded by viral genes tend to change slowly, making it possible to detect these hidden evolutionary connections. However, until the advent of tools like AlphaFold, which can predict protein structures on a large scale, it was not possible to compare protein structures across an entire family of viruses, says Joe Grove, a molecular virologist at the University of Glasgow, UK.

In an article published this week inNature 1Grove and his team demonstrate the power of a structure-based approach to flaviviruses—a group that includes hepatitis C, dengue, and Zika viruses, as well as several important animal pathogens and species that may pose emerging threats to human health.

How viruses invade

Researchers' understanding of flavivirus evolution is based primarily on sequences of slowly evolving enzymes that copy their genetic material. However, remarkably little is known about the origins of the “viral entry” proteins that flaviviruses use to enter cells and that determine the host they can infect. Grove argues that this knowledge gap will hinder the development of an effective vaccine against Hepatitis C, which kills hundreds of thousands of people every year.

“At the sequence level, things are so divergent that we can’t say whether they’re related or not,” he says. “The breakthrough in protein structure prediction opens up the whole question, and we can see things pretty clearly.”

The researchers used DeepMinds AlphaFold2 -model and ESMFold, a Structure- Prediction tool developed by tech giant Meta, to generate more than 33,000 predicted structures for proteins from 458 flavivirus species. ESMFold is based on a language model trained with tens of millions of protein sequences. Unlike AlphaFold, it only requires one input sequence rather than relying on multiple sequences of similar proteins, which could make it particularly useful for studying the most mysterious viruses.

The predicted structures allowed the authors to identify viral entry proteins whose sequences differ greatly from those of known flaviviruses. They found some unexpected connections. So the group of viruses that includes hepatitis C uses a system to infect cells similar to what they discovered with the pestiviruses — a group that includes the classic swine flu virus, which causes hemorrhagic fever in pigs, and other animal pathogens.

The AI-powered comparisons showed that this input system is different from that of many other flaviviruses. "For hepatitis C and its relatives, we don't know where their entry system comes from. It could have been invented," says Grove.

Stolen by bacteria

The predicted structures also showed that the well-studied input proteins of Zika and dengue viruses have the same origins as those of the "weird and wonderful" flaviviruses with huge genomes, including the Haseki tick virus, which can cause fever in humans. Another big surprise was the discovery that some flaviviruses possess an enzyme that appears to have been stolen from bacteria.

"This would be unprecedented," says virologist Mary Petrone of the University of Sydney, Australia, were it not for her team's discovery this year of a similar theft of a particularly "weird and wonderful" species of flavivirus 2. “Genetic piracy may have played a larger role in the evolution of flaviviruses than previously thought,” she adds.

David Moi, a computational biologist at the University of Lausanne, Switzerland, says the flavivirus study is just the tip of the iceberg and that the evolutionary stories of other viruses and even some cellular organisms are likely to be retold using AI. “Now that we can take a look further, all of these things need to get a little update,” he says.

Suche

Suche

Mein Konto

Mein Konto