After decades of dreaming about Jupiter's moon Europa and the vast ocean that likely lies hidden beneath its icy surface, scientists are now close to sending a spacecraft there. NASA confirmed yesterday that the Europa Clipper mission will launch as planned after concerns there could be significant delays due to potentially faulty transistors on the $5 billion spacecraft.

“We are confident that our beautiful spacecraft and capable team are ready for launch operations and our comprehensive science mission to Europa,” said Laurie Leshin, director of NASA's Jet Propulsion Laboratory (JPL) in Pasadena, California, at a press conference on September 9.

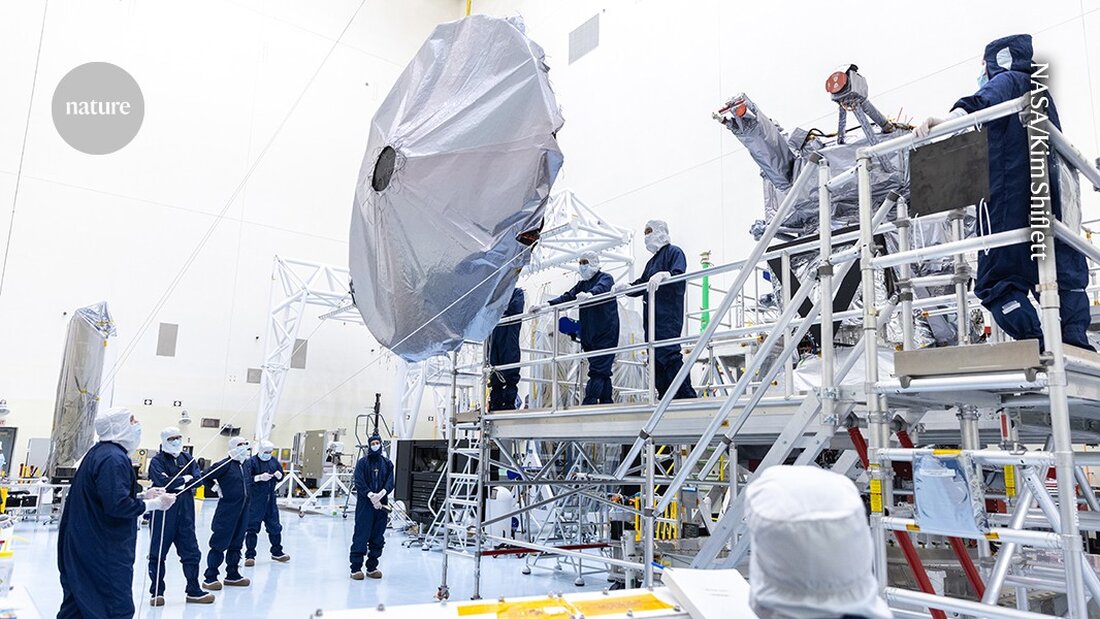

With a mass of over 3.2 tons, a height of about 5 meters and a width of more than 30 meters with the solar panels fully deployed, Europa Clipper is the largest spacecraft NASA has ever built for a planetary mission. Yesterday the mission passed what is known as “Key Decision Point E” — the final check that must be completed before launch. The launch window for the spacecraft begins October 10th.

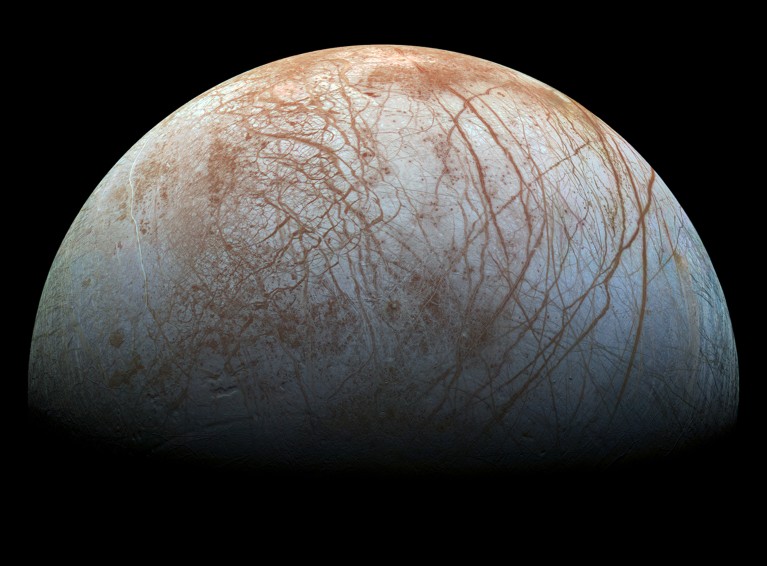

If the orbiter successfully lifts off next month, it will reach Jupiter in April 2030. Its nine instruments will then study both Europa's icy crust and the ocean that scientists believe lies beneath it, to determine whether the moon could support life as we know it. Previous missions have indicated 1, that Europa's icy surface hides a subterranean ocean of saline water with more than twice the amount of water in Earth's oceans. The moon's cracked, seemingly young surface also suggests that the satellite has an active geology — suggesting that Europa's interior may be warm and dynamic enough for the complex chemistry of life.

“There is no device like a tricorder – a fictional instrument from the Star Trek universe – that we can point at something to show whether it is alive,” said Curt Niebur, the Europa Clipper program scientist at NASA Headquarters in Washington DC, during the press conference. “It is extremely difficult to detect life, especially from orbit,” he added. “First we will ask the simple question: Are the right ingredients present for life to exist?”

Difficulties on the way to an ocean world

Prior to the transistor-related concerns, Europa Clipper had already experienced a number of setbacks. 2019 NASA angered scientists by removing a complex magnetometer from the spacecraft and justified this with budget problems. The mission also faced years of uncertainty about how it would get to space. That's because Congress had long mandated that the spacecraft fly aboard NASA's slower-than-expected Space Launch System rocket. Finally, in 2020, U.S. lawmakers allowed the program to select private company SpaceX's reliable Falcon Heavy rocket in Brownsville, Texas, for launch.

The possible transistor problem occurred in May of this year, when NASA engineers learned that batches of a particular type of transistor already installed on the Europa Clipper spacecraft were not functioning properly. These components, called MOSFETS (metal-oxide-semiconductor field-effect transistors), act like switches in electrical circuits. They come from a NASA supplier, Infineon, based in Neubiberg, Germany.

Because the Europa Clipper will fly near Europa 49 times, flying at distances of up to 25 kilometers, the spacecraft must also fly through a volley of charged particles accelerated by Jupiter's magnetic field, which is about 20,000 times stronger than Earth's. This means that the electronics in the orbiter must be radiation resistant.

However, in May, NASA said it was evaluating whether the mission's transistors posed a risk of malfunction. The agency launched four months of intensive, round-the-clock testing at three different locations: JPL; the Johns Hopkins Applied Physics Laboratory in Laurel, Maryland; and the NASA Goddard Space Flight Center in Greenbelt, Maryland. “This has been a huge challenge, and I think ‘huge challenge’ is a massive understatement,” Leshin said.

After evaluating replacement MOSFETs from the same batches installed on the Europa Clipper, NASA determined that the spacecraft's circuits would function as expected. This conclusion is based in part on the fact that during the first half of its basic four-year mission, while orbiting Jupiter, the spacecraft will enter Jupiter's strongest radiation only once every 21 days. The rest of the time, the orbiter's transistors can partially heal themselves when gently heated, through a process called recrystallization.

"As Europa Clipper enters the radiation environment, it comes back out, long enough for these transistors to have a chance to regenerate and partially recover between flybys," Jordan Evans, Europa Clipper's project manager at JPL, said during the conference. “We can — I have great confidence in this, and the data confirms this — complete the original mission.”

Suche

Suche

Mein Konto

Mein Konto