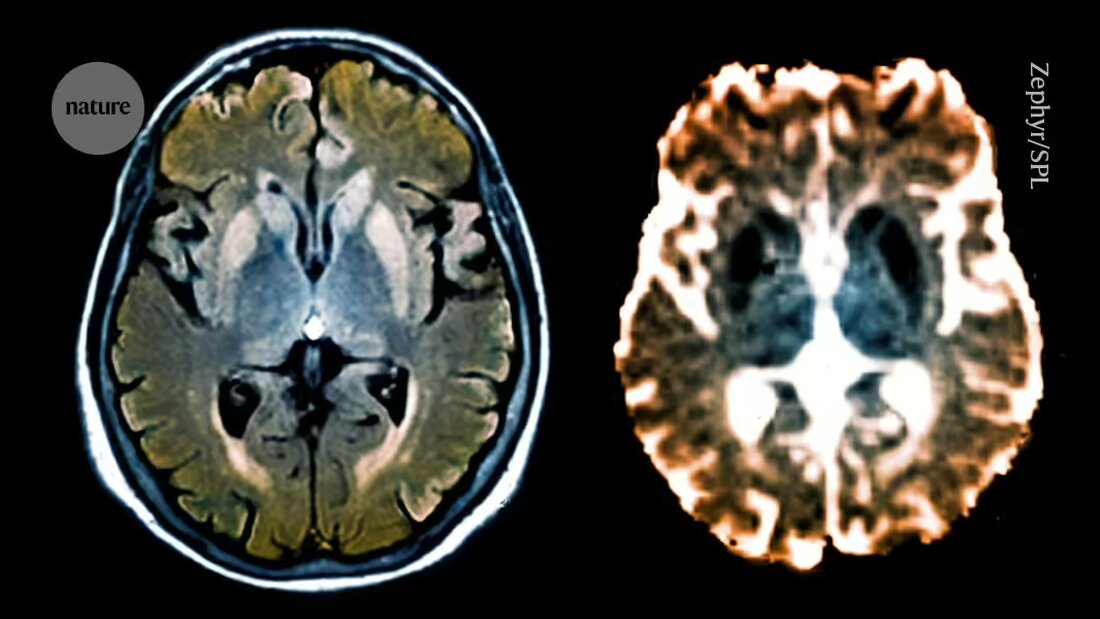

A molecular editing tool small enough to be delivered into the brain stops production of proteins that cause prion diseases, a rare but deadly group of neurodegenerative disorders.

The system – known as a “coupled histone tail for automatic release of methyltransferase (CHARM)” – alters the 'epigenome', a collection of chemical tags bound to DNA that influence gene activity. In mice, CHARM silenced the gene that produces the harmful proteins that cause prion diseases in most neurons in the brain, without changing the gene sequence.

CHARM is the first step toward developing a safe and effective "one-time treatment" to reduce levels of disease-causing proteins, says Madelynn Whittaker, a bioengineer at the University of Pennsylvania in Philadelphia. The results were announced todayScience 1published.

“The system addresses significant challenges faced by previous epigenetic editing systems,” says Whittaker, accompanying an perspective article inScienceco-authored. These include reducing the toxicity of editing tools and delivering them to cells without compromising their effectiveness, she adds.

Prion diseases are caused by misfolded prion proteins (PrPs) that clump together and destroy neurons. This can lead to conditions such as fatal familial insomnia syndrome - a rare genetic disease that prevents people from sleeping and leads to death. Although prion diseases are incurable, drugs called antisense oligonucleotides (ASOs) have shown some promising results. These short, single-stranded molecules bind to faulty messenger RNA sequences and increase or decrease protein expression. Previous studies in mice infected with misfolded versions of PrP have shown that ASOs reduce the expression of these proteins and extend lifespan 2. But the drugs require multiple injections to achieve a long-term therapeutic effect and can lead to side effects such as liver damage, Whittaker says.

In 2021, Jonathan Weissman, a biochemist at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology in Cambridge, and his team developed CRISPRoff 3– an editing tool that adds a chemical tag called a methyl group to the DNA strand, which reduces gene activity without altering the genome. But the tool can't be delivered to brain cells because its genetic components are too large to fit into an adeno-associated virus (AAV) - a common vehicle for delivering gene therapies into cells. “The real challenge was delivery,” says Weissman.

New editor

To solve this, Weissman and his team developed CHARM, which uses molecules called zinc finger proteins to direct itself to target genes. These proteins are small enough to be delivered in an AAV vector.

The researchers modified CHARM to recruit and activate components of DNA methyltransferases - molecules found in cells that attach methyl groups to DNA, causing the gene expression change. This reduces the toxic effects associated with adding molecules from outside the cell, says Weissman. “The only thing we changed in the cell was its ability to express the prion protein,” he says.

When the researchers delivered CHARM into the brains of healthy mice, they found that it reduced PrP expression throughout the brain by more than 80% - well above the minimum level required for a therapeutic effect. Weissman and his team also designed CHARM to shut down after it finishes its silent work, preventing it from making copies of itself that could lead to harmful side effects.

The team behind CHARM includes Sonia Vallabh and her husband Eric Vallabh Minikel, prion scientists at the Broad Institute of MIT and Harvard University in Cambridge. Vallabh inherited the mutation behind the fatal familial insomnia syndrome, and twelve years ago Vallabh and Minikel switched careers to investigate treatments for the disease. Vallabh says CHARM brings her “tremendous confidence”. She adds that drug development is typically slow, but the work shows how quickly new approaches can be developed with the right team. “The scale of what you can achieve in a short period of time is incredible,” says Vallabh. “It was only two years and a month ago that we first presented Jonathan with the idea of working together and now here we are.”

CHARM also has the potential to treat other diseases caused by the buildup of abnormal proteins, such as Parkinson's and Alzheimer's, Weissman adds. “We know that epigenetic silencing does not work for every gene, but for the majority of genes,” he says.

Jacob Goell, a researcher developing epigenome editing tools at Rice University in Houston, Texas, is optimistic that CHARM will one day end up in the clinic. But more comprehensive work is needed to evaluate how the tool and the changes it creates interact with the cells' genetic machinery, particularly over longer periods of time, he adds.

The next step is to study how CHARM works in an AAV vector that can target neurons in the human brain. “This is the next big challenge,” he says.

Suche

Suche

Mein Konto

Mein Konto