After the social media platform X was banned in Brazil last week, scientists in the country began frantically searching for another online forum to post about their research, communicate with colleagues, and stay up-to-date on scientific advances. “Following journals and important people is what keeps me up to date,” says Regina Rodrigues, a physical oceanographer at the Federal University of Santa Catarina in Florianópolis, Brazil.

Some feel isolated because of the change. “I lost contact with colleagues and European research groups that I joined during my postdoctoral studies in Spain,” says Rodrigo Cunha, a communications researcher at the Federal University of Pernambuco in Recife, Brazil.

Others are more relaxed and point out that many researchers have already done so X (formerly Twitter)., after billionaire Elon Musk bought it and changed its policies, including those on content moderation and confirming users as “verified” or an authoritative source of information. Sabine Righetti, a science communications researcher at the State University of Campinas in Brazil, left the platform early last year due to what she perceived as an increase in aggressive messaging, particularly against scientists, journalists and women. “I am all three of those things,” she says.

Ronaldo Lemos, principal scientist at the Institute of Technology and Society in Rio de Janeiro, says the ban could provide a glimpse into what the world would be like without X. Social networks come and go, he says, pointing to some that have closed, such as Google's Orkut, which closed in 2014 and was once popular in Brazil. “People are adapting and looking for ways to reconstruct their networks in other places,” he says.

Free expression

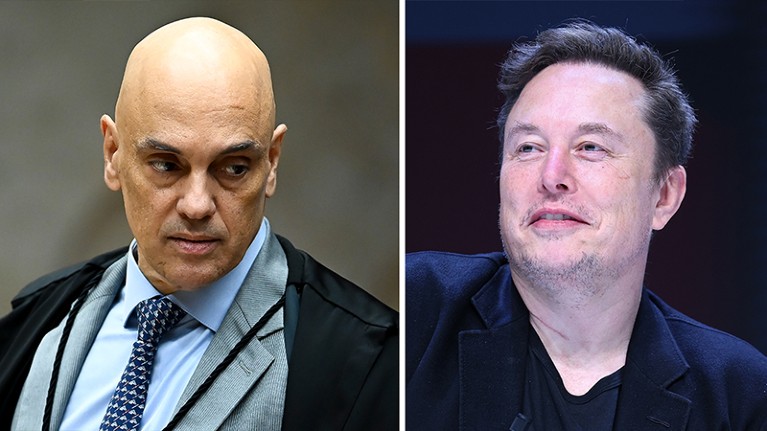

On August 30, Brazilian Supreme Court Justice Alexandre de Moraes ordered the ban after a months-long conflict with Musk over the limits of freedom of expression.

Early last month, de Moraes issued a court order shutting down a number of accounts seen as spreading disinformation and destabilizing Brazil's democracy. The company failed to comply and closed its office in Brazil about two weeks later. De Moraes then issued an order requiring X to appoint a new legal representative in the country since the previous one had failed to comply with court orders. X ignored the order, which led to the ban. Last week, Brazil's Supreme Court upheld de Moraes' sentence - which includes a fine of $9,000 per day for any of Brazil's over 200 million people caught using X via a virtual private network (VPN) or other means. (A VPN typically encrypts a user's data and disguises their IP address.) That's more than most Brazilians earn in a year.

For years, scientists have been using X not just to Comments on research, conversations with colleagues and the search for new employees but also to promote their work and correct misunderstandings. For example, during the COVID-19 pandemic, Átila Iamarino, a microbiologist and science communicator in São Paulo, Brazil, became a preferred source on the SARS-CoV-2 coronavirus, reaching more than a million followers. “It was the place where I engaged with colleagues, put together arguments for live broadcasts and debunked misinformation as it came out.”

Karina Lima, a climatologist at the Federal University of Rio Grande do Sul in Porto Alegre, Brazil, misses the platform because it was a place where she got opportunities and reached many people through her science communication work. But it recognizes that social media should not be “a lawless space that fosters hate speech and disinformation.”

On trial somewhere else

Despite the increase in this type of news after Musk's takeover 1some researchers stuck with it. Letícia Sallorenzo, a linguistics researcher at the University of Brasília, still found the tool useful. Before the ban, she happened to be studying online hate speech aimed at de Moraes. The ban has barred her from this work, and she must ask the court to allow her to use X over a virtual private network to continue.

Scientists outside Brazil are also feeling the loss of X in the country. Although it had become a less reliable network for scientists, "There are Brazilian researchers and institutions I can collaborate with," says Jonathan Vicente, a climate change and health researcher at the University of Bern in Switzerland.

More than two million people in Brazil have now moved to another social media platform called Bluesky. “It's the platform that most resembles Twitter when it started,” says Iamarino. Scientists are also trying it out, as well as other platforms like mastodon and threads, says Lemos. The good news is that “it’s not like Twitter has stopped and there’s no alternative,” he adds.

But rebuilding social networks online can be difficult, especially for researchers from low-income countries that have little visibility, says Rodrigues. “It's hard to build a network of colleagues, especially if you're not a household name,” she says.

For Iamarino, it becomes clear which platform has won among users when they start checking messages on it before going to sleep. He begins to feel this way about Bluesky. “I put the app where Twitter used to be on my phone,” he says.

Suche

Suche

Mein Konto

Mein Konto