Scientist treats her own cancer with lab-grown viruses

A virologist successfully treated her breast cancer with lab-grown viruses, raising ethical questions about self-experimentation.

Scientist treats her own cancer with lab-grown viruses

A scientist who successfully creates her own Breast cancer by injecting the tumor with laboratory-grown viruses has sparked debate about the ethics of self-experimentation.

Beata Halassy discovered in 2020 at the age of 49 that she had breast cancer at the site of a previous mastectomy. This was her second return to the site since her left breast was removed and she did not wish to undergo further chemotherapy.

Halassy, a virologist at the University of Zagreb, studied the literature and decided to take matters into her own hands with an unproven treatment.

A case report published in the journal Vaccines in August 1 describes how Halassy offers a treatment called oncological virotherapy (OVT) herself used to treat her own stage 3 cancer. She has been cancer-free for four years.

By Halassy deciding Self-experiments She joins a long list of scientists involved in this neglected, stigmatized and ethically problematic practice. “It took a brave editor to publish the report,” says Halassy.

Emerging therapy

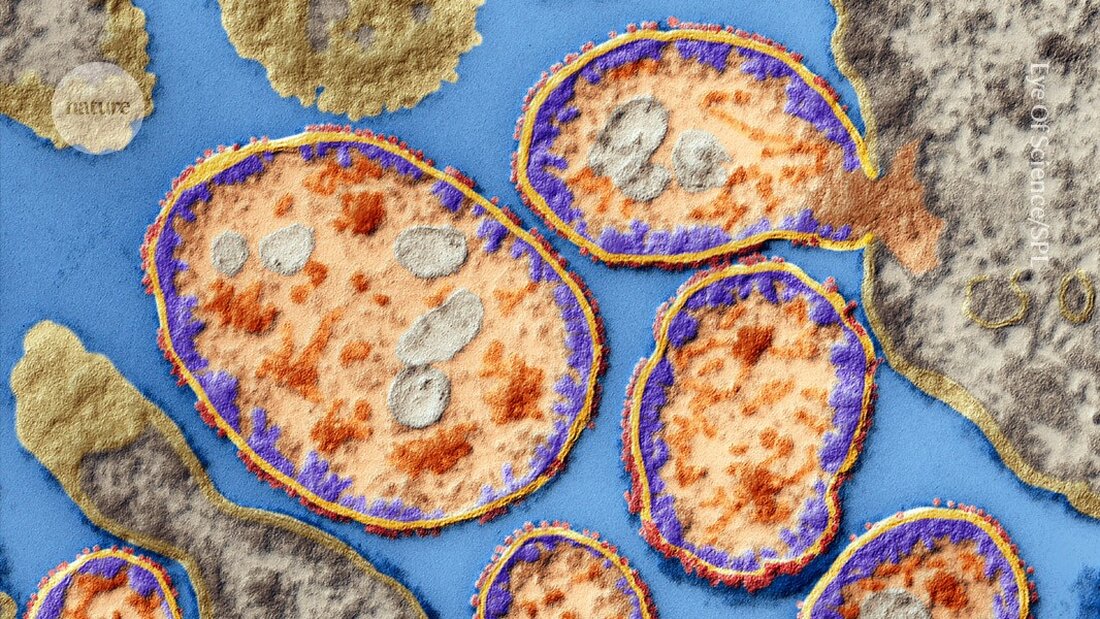

OVT is an emerging field of Cancer treatment, in which viruses both attack cancerous cells and stimulate the immune system to fight them. To date, most OVT clinical trials have been in advanced metastatic cancer, but in recent years they have increasingly been targeted at earlier stages of disease. An OVT, called T-VEC, has been approved in the United States to treat metastatic melanoma, but there are currently no approved OVT agents to treat breast cancer at any stage worldwide.

Halassy emphasizes that she is not a specialist in OVT, but her expertise in culturing and purifying viruses in the laboratory gave her the confidence to try the treatment. She decided to treat her tumor with two different viruses, one at a time Measles virus, followed by vesicular stomatitis virus (VSV). Both pathogens are known to infect the cell type from which their tumor originates and have already been used in OVT clinical trials. A measles virus was tested against metastatic breast cancer.

Halassy already had experience working with both viruses, both of which have a good safety profile. The measles virus type she chose is used extensively in childhood vaccines, and the VSV type causes at most mild flu-like symptoms.

Over a two-month period, she was administered a treatment regimen by a colleague using research-grade material freshly prepared by Halassy and injected directly into her tumor. Her oncologists agreed to monitor her during self-treatment so that she could switch to conventional chemotherapy if something went wrong.

The approach appeared to be effective: over the course of treatment, without serious side effects, the tumor shrank significantly and became softer. It also separated from the pectoral muscle and skin into which it had grown, making surgical removal easier.

Analysis of the tumor after its removal showed that it was thoroughly permeated with immune cells called lymphocytes, suggesting that the OVT had worked as expected, stimulating Halassy's immune system to attack both the viruses and the tumor cells. “An immune response was definitely triggered,” says Halassy. After the operation, she received the cancer medication trastuzumab for a year.

Stephen Russell, an OVT specialist who runs the virotherapy company Vyriad in Rochester, Minnesota, agrees that Halassy's case suggests that the viral injections helped shrink her tumor and shrink its invasive edges.

However, he doesn't believe their experience is groundbreaking, as researchers are already trying to use OVT to treat cancer in earlier stages. He's not sure if anyone has tried two viruses in a row before, but says it's not possible to determine whether that played a role in a study size of n=1. “Honestly, the new thing is that she did it herself with a virus that she grew in her own lab,” he says.

Ethical dilemma

Halassy felt compelled to publish her results. But she received more than a dozen rejections from journals—mainly, she says, because the work she was writing with colleagues involved self-experimentation. “The main concern was always ethical issues,” says Halassy. She was particularly determined to persevere after finding a review highlighting the value of self-experimentation 2.

That the journals had concerns surprises Jacob Sherkow, a law and medicine researcher at the University of Illinois Urbana-Champaign who has studied the ethics of self-experimentation in COVID-19 vaccine research.

The problem isn't that Halassy was doing self-experimentation, but that publishing her results could encourage others to reject conventional treatments and try something similar, Sherkow says. People with cancer are particularly vulnerable to trying unproven treatments. However, he points out that it is also important to ensure that the knowledge gained from self-experimentation is not lost. The article emphasizes that self-medication with cancer-fighting viruses “should not be the first approach” in the event of a cancer diagnosis.

“I think it ultimately falls into the ethical category, but it's not a clear-cut case,” Sherkow says, adding that he wishes there had been a commentary on the ethical perspective that appeared alongside the case report.

Halassy has no regrets about her self-medication or her relentless drive to publish. She doesn't think anyone would try to follow her lead since the treatment requires a lot of scientific knowledge and expertise. And the experience has given her own research a new direction: In September, she received funding to study OVT as a treatment for cancer in pets. “The focus of my lab has completely changed because of the positive experience with my self-treatment,” she says.

-

Forčić, D. et al. Vaccines 12, 958 (2024).

-

Hanley, B.P., Bains, W. & Church, G. Rejuv. Res. 22, 31–42 (2019).

Suche

Suche

Mein Konto

Mein Konto