Like actors and writers, researchers experience their fair share of rejection. Scientists submit their work to journals hoping it will be accepted, but many manuscripts are rejected by the preferred publication and ultimately accepted by another. A significant number of submissions never find a home.

A study 1illuminates this process of rejection and resubmission, which she sees as influenced by the different attitudes and behaviors of researchers around the world.

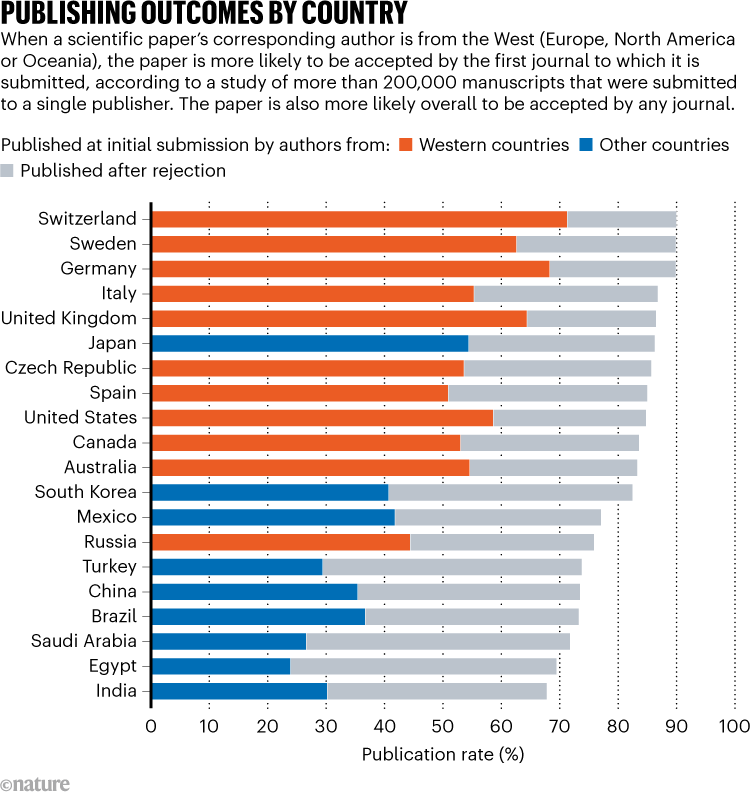

After tracking the fate of around 126,000 rejected manuscripts, the research team found that authors in Western countries are almost 6% more likely than those in other parts of the world to successfully publish a paper after a rejection. This, the authors suggest, could be due to regional differences in access to 'procedural knowledge' of how to deal with rejections - how to interpret negative reviews, revise accordingly and resubmit to a journal that is likely to accept the work. (Many scientific journals are based in Western countries.)

“Maybe it's about being in the right networks and getting the right kind of advice at the right time,” says Misha Teplitskiy, co-author and sociologist who studies innovation in science and technology at the University of Michigan in Ann Arbor.

Rejection review

Teplitskiy and his colleagues worked with data from IOP Publishing (IOPP), a company based in Bristol, UK, that publishes more than 90 English-language journals and is owned by the Institute of Physics.

They examined around 203,000 manuscripts submitted to 62 of IOPP's physical sciences journals between 2018 and 2022. Around 62% were rejected. The researchers searched a bibliometric database to see if the same (or similar) work was later published elsewhere. They then ranked these publications by the geographical region of the corresponding author—the researcher typically responsible for the publication process of a study—and compared the results for authors from the West (which they define as North America, Europe, and Oceania) with those from the rest of the world.

To compare the fate of rejected papers as fairly as possible, the authors categorized them by quality based on the original reviewers' ratings and comments recorded in the IOPP data. This allowed them to 'compare like with like': for example, whether inferior papers by authors from the West had different results than those judged to be of comparable quality but written by authors from other parts of the world.

The analysis – before peer review as a preprint on the SSRN server 1published – showed that corresponding authors from Western countries are 5.7% more likely to publish a manuscript after rejection than those from other regions. In a process that often took up to 300 days, they did this an average of 23 days faster. These authors also revised their manuscript's abstract - a proxy for the overall paper - 5.9% less often, as defined by a calculated 'edit distance' metric. And ultimately they published in journals with 0.8% higher impact factors. This metric reflects how often papers in a journal are cited, but is equated by some with the reach and prestige of the journal.

Breaking it down by country, the team's analysis showed that around 70% of papers from Asian nations such as China and India were ultimately published, compared to 85% from the United States and almost 90% for many European countries (see 'Publication expenditure by country').

What accounts for these differences is difficult to say, says Teplitskiy, but the results are consistent - at least in part - with the idea that the tacit norms and rules of the publishing process are more widely circulated in the West, leading to a higher likelihood of successful responses to rejections by Western scientists. His team tried asking the authors of rejected papers about this hypothesis in a follow-up survey, but received few responses.

Navigate the system

The way the authors rated and compared papers of similar quality is a good approach, says Honglin Bao, a data scientist at Harvard Business School in Boston, Massachusetts, who previously worked in China: "I think it works."

Differences in procedural knowledge could contribute to the well-known bias in the peer review system against researchers from non-Western countries, says Bao. Another possibility is that cultural factors work against researchers and contribute to bias in the system. For example, many magazines are written in English, which puts researchers whose native language is not English at a disadvantage and could contribute to their poorer performance following rejection.

Teplitskiy will now face the potential rejection-resubmission cycle himself. He has the study for peer review at the journalProceedings of the National Academy of Sciencessubmitted but is realistic about the likely outcome. “I think this paper is great, but I know the process is noisy,” he says. “We expect it will initially bounce back and forth and then land somewhere.”

Suche

Suche

Mein Konto

Mein Konto