Lethal Marburg virus spreads in Rwanda: Why scientists are worried

Marburg virus is spreading in Rwanda, worrying scientists about high mortality and the increase in such outbreaks.

Lethal Marburg virus spreads in Rwanda: Why scientists are worried

It is an outbreak of superlatives. One of the deadliest viruses known, Marburg, appeared in Rwanda, has killed 13 people and sickened 58 in one of the largest Marburg outbreaks ever documented. Scientists expect the outbreak to be contained quickly - but warn that Marburg as a whole is on the rise.

The outbreak, which was declared on September 27th, is Rwanda's first. Tanzania and Equatorial Guinea recorded its first Marburg outbreaks last year; Ghana's first outbreak was in 2022. Before the 2020s, outbreaks were detected at most a few times per decade; today they occur about once a year. The causes of these events are not completely clear. Researchers explain that environmental threats such as climate change and Deforestation, increasing the likelihood of people encountering animals that can carry diseases.

Outbreaks of animal-borne diseases “will continue to occur more frequently,” says emergency medicine physician Adam Levine of Brown University in Providence, Rhode Island. “The world really needs to adapt to this.”

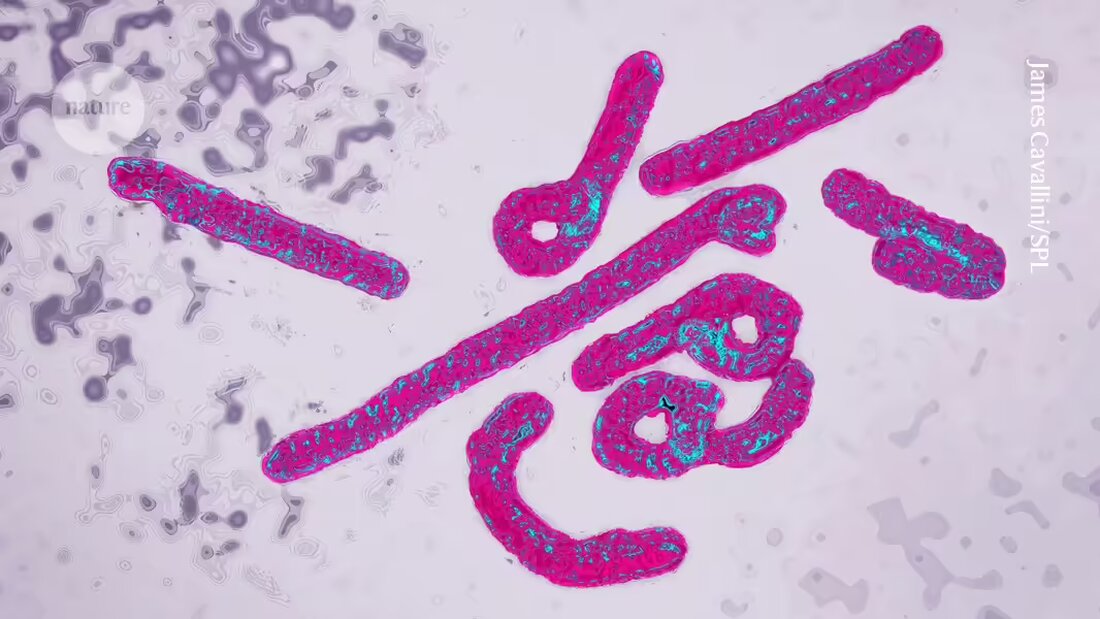

The Marburg virus is a “cousin” of the Ebola virus, which killed more than 11,000 people in West Africa between 2014 and 2016 explains virologist Adam Hume from Boston University in Massachusetts. The mortality rate at Marburg has ranged from 23% to around 90% in past outbreaks. There are no vaccines or treatments, but supportive care increases the chances of survival.

Early symptoms of Marburg – high fever, headache and malaise – are similar to many other illnesses. But people with Marburg soon develop severe diarrhea, nausea and vomiting. Those most severely affected bleed from the nose, gums or other parts of the body.

In Rwanda, some of the first people who later tested positive for Marburg had initially tested for malaria. Health workers realized something was wrong when usual treatment didn't work. By the time the workers realized they were dealing with a Marburg outbreak, several of them had already become infected, Rwandan Health Minister Sabin Nsanzimana said in a news conference last week.

The outbreak is concerning residents of Kigali, says Olivia Uwishema, the Rwandan-born founder of the Oli Health Magazine Organization, a non-profit organization in Kigali. Uwishema lives in the United States but happened to be in Kigali when Marburg arrived. Now people think when someone has a fever “that it might be Marburg,” says Uwishema.

The good news is that Marburg is primarily transmitted through contact with bodily fluids. This means that isolating infected people and using protective equipment can effectively contain the spread, says Levine.

Over the next three weeks, contact tracers in Rwanda will speak to hundreds of people who have had direct or indirect contact with Marburg infected people. Health workers test everyone who comes to the clinic with a high fever for the disease. This puts a strain on the country's diagnostic laboratories due to the high incidence of malaria.

Rwanda's extensive testing for the virus may be responsible for the large size of the current outbreak. Many past outbreaks have been reported that affected only a few people, explains Uwishema. But cases may have been missed in countries whose health systems are not strong enough to provide the level of testing that Rwanda has achieved.

The outbreak can be declared over if no new infections occur within 42 days - which corresponds to two incubation periods of the virus - after the last identified case. “In the coming weeks we should have a good sense of whether it is rising quickly or declining,” says Levine.

Marburg outbreaks usually begin after a person encounters an infected fruit bat – an animal that can carry the virus without becoming ill. Due to influences such as climate change and deforestation, "the boundaries between wildlife and humans are collapsing," creating increasingly frequent opportunities for pathogens to jump to humans, said global health expert Caroline Ryan of Ireland's Ministry of Agriculture, Food and Marine Resources in Celbridge.

Vaccines and drugs could help contain Marburg, but to thoroughly test these agents, scientists have to wait for outbreaks. "That's one of the reasons why I don't think we have any therapeutics or vaccines approved against Marburg virus," Hume said.

Rwandan doctors have started testing a vaccine candidate against Marburg and plan, to test the effectiveness of the antiviral drug remdesivir against the disease. Animal testing 1 suggest that remdesivir could be helpful to treat Marburg, as is the case with COVID-19. But data from human trials examining remdesivir as a treatment for Ebola "were a little disappointing," Hume says, raising the prospect that the drug might not be useful for Marburg either.

But identifying an effective antiviral alone will not be enough, health officials say. To deal with future outbreaks, must Africa's vaccine production capacity, treatments and diagnostic tools on their own, said Jean Kaseya, director general of the Africa Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, last week. Relying on other countries to sell such supplies at high prices can lead to “panic mode,” he said.

-

Porter, D. P., et al. J. Infect. Dis. 222, 1894–1901 (2020).

Suche

Suche

Mein Konto

Mein Konto