From much-maligned garden snails and snails to tool-using octopuses and bivalves such as mussels and oysters, molluscs are among the most diverse groups of animals on the planet. But their origins are a mystery.

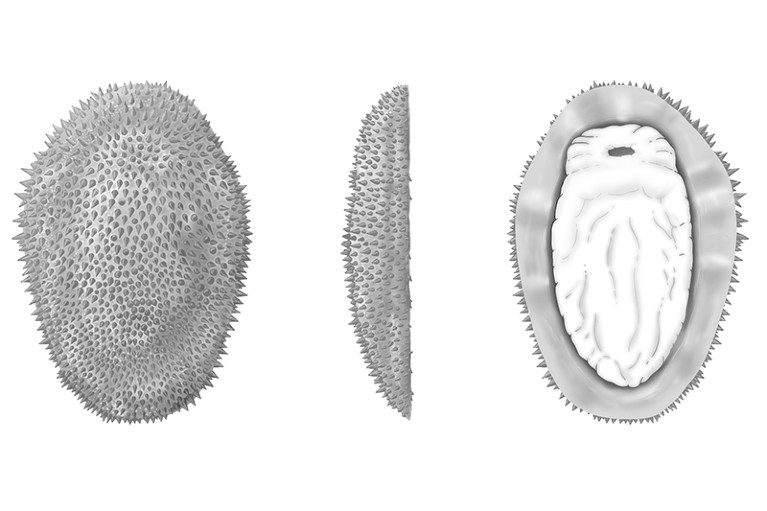

A newly discovered mollusc fossil - which resembles a durian fruit sliced lengthwise - provides clues to what the earliest species may have looked like. “They were some kind of strange, spiny snail,” says Luke Parry, a paleontologist at the University of Oxford, UK, who is part of the team that discovered the approximately 510 million-year-old fossilsSciencedescribed on August 1st 1.

Like many other animal groups Molluscs also exploded in diversity during the Cambrian, 539 to 485 million years ago, and almost all groups found on Earth today emerged during this time.

But this rapid pace of change makes it difficult to determine the characteristics of early molluscs, according to Parry. “Just from the sight of a modern mussel and a modern octopus, it is difficult to imagine what their common ancestor might have looked like.”

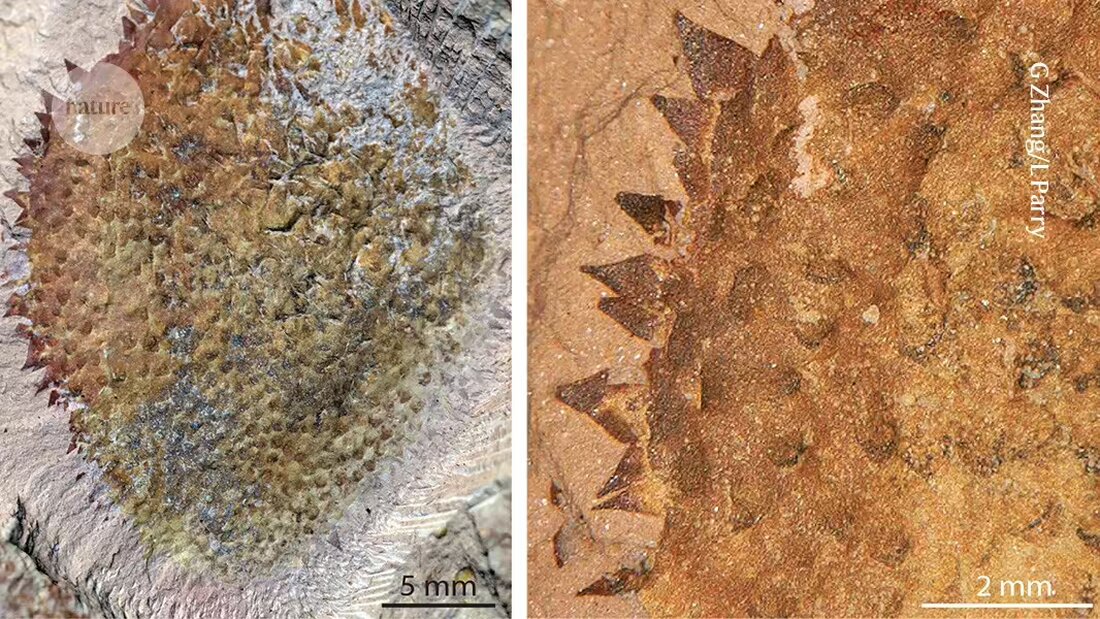

The durian fruit-like mollusk fossils, a few centimeters in diameter, were discovered at a road construction site in Kunming, China. Study co-author Guangxu Zhang, a paleontologist at Yunnan University in Kunming who was getting his doctorate at the time, thought the first specimen he found resembled a rotting plastic bag. "It wasn't immediately important or noticeable," says his advisor Xiaoya Ma, a paleontologist at the University of Exeter in Penryn, UK, who is also a co-author of the study.

But additional, better-preserved specimens revealed the creature's soft underside, including features found in modern molluscs, such as a foot. The top of the mollusk was covered in hollow chitinous spines - an organic compound that also forms the exoskeletons of insects. The researchers named the speciesShishania aculeata, named after Yunnan Province's renowned geologist Shishan Zhang, now 87 years old.

Hollow chitinous spines in early molluscs such asShishaniaprobably gave rise to calcium carbonate shenanigans, which in modern molluscs are called beetles. The spines also appear to share an origin with chitinous bristles covering segmental worms in a distantly related invertebrate group called annelids.

“This is really another piece of the puzzle,” says paleobiologist Mark Sutton at Imperial College London. “It helps to express our ideas about the evolution of molluscs, and we finally get a coherent story.”

The spines, which could also have been sensory organs, probably helpedShishaniaand other early molluscs to avoid predators as they crawled across the Cambrian seafloor, says Parry. “The fact that we have these fossils is pretty amazing.”

Suche

Suche

Mein Konto

Mein Konto