Google uses millions of smartphones to map the Earth's ionosphere and improve GPS

Google is using real-time data from 40 million smartphones for the first time to map the ionosphere and improve GPS accuracy worldwide.

Google uses millions of smartphones to map the Earth's ionosphere and improve GPS

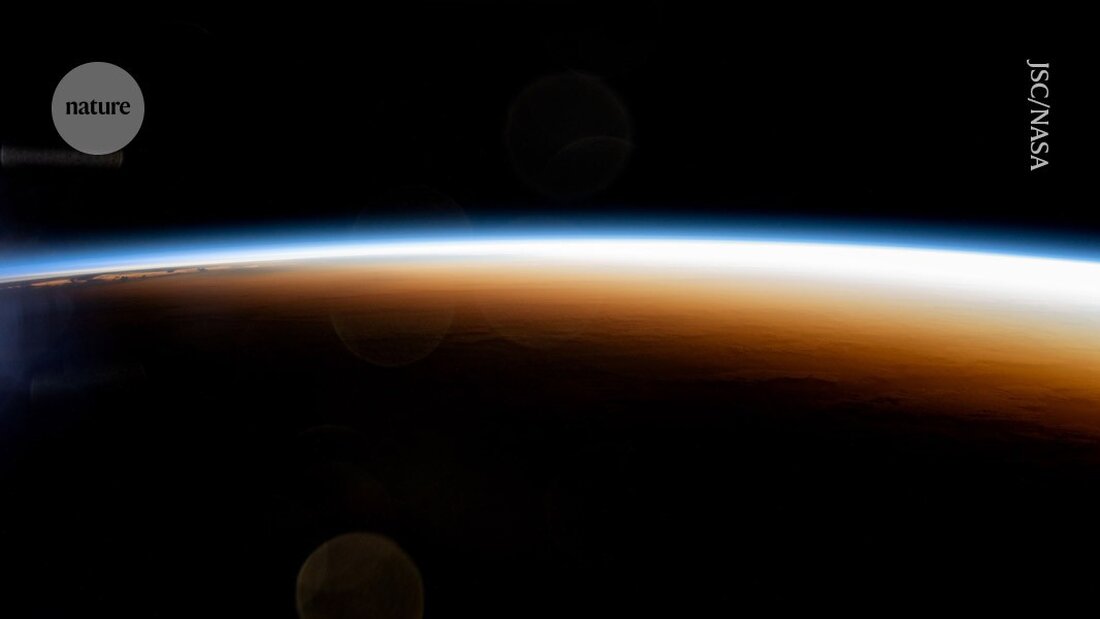

For the first time, researchers have used real-time data from around 40 million cell phones to map conditions in the ionosphere — a region of the upper atmosphere where some air molecules are ionized. Such crowdsourced signals could improve satellite navigation, particularly in regions of the world where data is otherwise scarce, such as Africa, South America and South Asia.

The Google team's feasibility study was published November 13 in the journal Nature 1.

“It's an amazing data set,” says Anthea Coster, an atmospheric physicist at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology in Cambridge. “It significantly completes the map in areas where we urgently need more information.”

Cell phone data could reduce GPS errors by 10-20% in some areas and even more in underserved regions, estimates Ningbo Wang, an atmospheric physicist at the Aerospace Information Research Institute of the Chinese Academy of Sciences in Beijing. Even with adjustments, ionospheric disruption remains a challenge, particularly during solar storms that trigger patchy conditions in the ionosphere. “The results presented are really impressive.”

Dual bands

When the air is partially ionized, the freely moving electrons slow down slightly and affect the radio signals that come to Earth from GPS and other navigation satellites. This can affect the nanosecond-level temporal synchronization used by satellite navigation devices to determine their locations. This has potentially serious implications for aircraft landings and autonomous vehicles.

Real-time maps of the density of these electrons are often used to correct for fluctuations in the ionosphere. Engineers create the maps using data from ground-based receiving stations that can detect the arrival times of two different frequencies of radio waves received from the same satellite. Electrons in the ionosphere slow down low-frequency waves more than high-frequency ones, by about a nanosecond. This difference provides information about the density of electrons through which the wave passed on its way to a receiver.

Without these corrections, GPS would be inaccurate by about 5 meters and by dozens of meters during solar storms, when charged particles from the sun increase electron density. But many regions of the world lack the ground-based receiving stations to create these maps.

background noise

Although not all navigation devices can work with multiple frequencies, modern phones often do. According to Brian Williams, a computer scientist at Google in Mountain View, California, and co-author of the study, phone sensors were not previously considered practical for mapping the ionosphere. This is because the data from cell phones is much noisier than that from specially designed scientific receiving devices, particularly because they only receive signals intermittently and the radio waves are reflected off nearby buildings in urban areas.

The Google team was successful in part thanks to the large amount of data they received. “When large amounts are combined, the noises cancel out and you still get a clear signal,” says Williams. “It’s like there’s a scientific monitoring station in every city where there are phones.”

Anyone who owns an Android phone and allows Google to collect sensor data to improve location accuracy could contribute to the study. However, the data was aggregated so individual devices cannot be identified, the company explains.

Williams explains that work is already underway to use this technique to improve location accuracy for Android users. But the data should also be useful for scientific studies of Earth's upper atmosphere. The map has already revealed bubbles in ionized gas, known as plasma, over South America that have not previously been observed in detail.

To truly benefit science, Google needs to publish the data, says Coster, who works on the Madrigal database, a collaborative geospatial data resource that brings together ionospheric data from thousands of ground stations. A Google spokesperson told Nature's news team that the data behind the study will be published alongside the article, but there are currently no plans to provide fresh data in real time.

Researchers are working on using other smartphone sensors in different ways. Google's Android earthquake warning system in 2020 showed how accelerometers in people's smartphones could detect earthquakes and warn others who could still be affected. Apple users can access an app that uses similar technology.

Until now, scientists have viewed phones as end-users of navigation services, says Wang. This reversal to use phone data as input data is “uncharted territory,” he says. “This study marks an exciting shift.”

-

Smith, J. et al. Nature 635, 365–369 (2024).

Suche

Suche

Mein Konto

Mein Konto