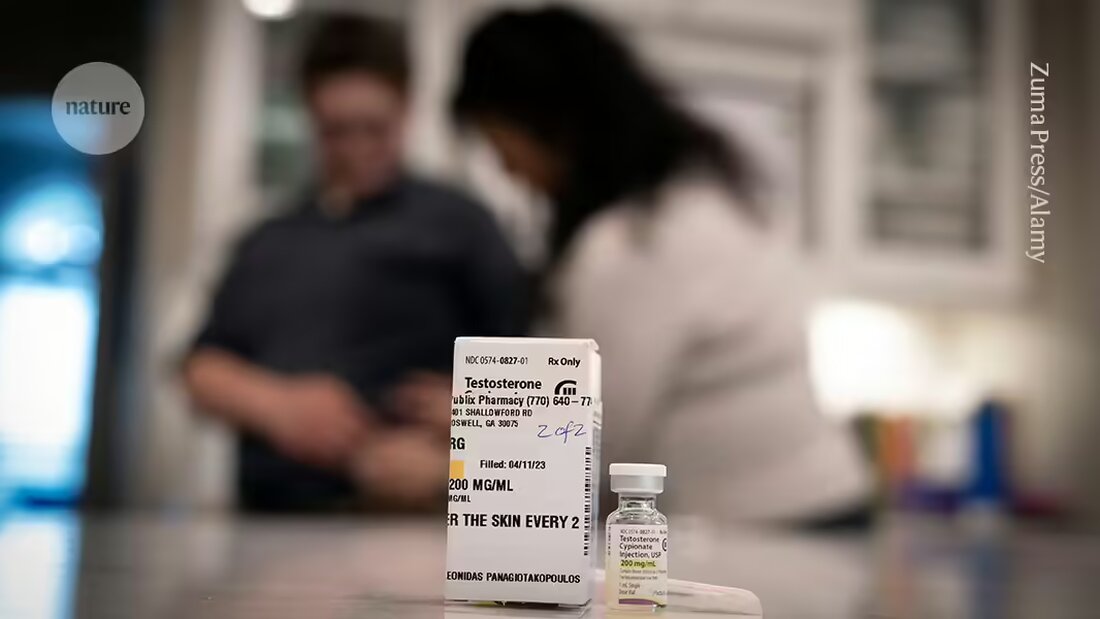

When trans men receive testosterone therapy, their bodies begin to resemble those of cis men in many ways – including their immune systems. This is what a study published today saysNature 1, one of the largest to date examining how gender-affirming hormone therapy (GAHT) affects the immune system over time.

The findings provide much-needed insight and could explain why men tend to be more susceptible to viral infections than women, and women are often more susceptible to autoimmune diseases.

The study is important because doctors want GAHT to be "naturally safe," says co-author Mats Holmberg, an endocrinologist at the Karolinska Institute in Stockholm, who provides gender-affirming care. It's a step toward being able to deliver the best possible treatment, says Holmberg.

An immunological balance?

During their study, Holmberg and his colleagues collected blood samples from 23 trans men (who were assigned female at birth but were seeking male GAHT) at three time points: before they started GAHT, three months after starting treatment, and one year after starting treatment. Over time, researchers observed a shift in the participants' immune response, from a type characterized by high levels of immune signaling proteins called type I interferons, which specialize in fighting viral infections, to one characterized by an abundance of an inflammatory protein called tumor necrosis factor (TNF), which is associated with muscle growth.

The news here is that sex hormones appear to cross-regulate immunological pathways, says study co-author Petter Brodin, a pediatric immunologist at the Karolinska Institutet. When testosterone levels rise and estrogen levels fall, it appears as if the immune system goes through a point of equilibrium, adds Brodin.

“This is a very interesting new finding that will trigger a lot of research,” says Marcus Altfeld, an immunologist at the University Hospital Hamburg-Eppendorf in Germany. In particular, Altfeld wants to understand whether increasing TNF levels directly reduce the amount of type I interferons or whether testosterone mediates both effects independently.

Disease effects

The researchers note that their findings reflect real-world susceptibility to infection and disease at the molecular level. For example, men infected with the SARS-CoV-2 coronavirus during the early days of the COVID-19 pandemic had a mortality rate about 50% higher than infected women. That makes sense, Brodin says, since women typically have high levels of Type I interferons, which help them fight off infections.

On the other hand, women are more likely to develop persistent COVID-19 than men — about 76% more likely, according to a study 2. This could be because persistent COVID-19 shares similarities with autoimmune diseases, some of which are associated with overactivation of the type I interferon system.

Other research also points in this direction. A pre-published study 3in March shows that low testosterone levels are a predictive factor in whether women will develop persistent COVID-19. “The importance of sex hormones in both acute, severe COVID and persistent COVID is increasingly recognized,” says preliminary study co-author Akiko Iwasaki, an immunologist at Yale University in New Haven, Connecticut.

But hormones probably aren't the whole story when it comes to differences in susceptibility to COVID-19 or other diseases, researchers say. The X chromosome — of which women typically have two copies and men have one — also deserves attention, says Sabra Klein, an immunologist at Johns Hopkins University in Baltimore, Maryland. The

Autoimmune risk

Trans men don't need to be too worried that testosterone therapy will increase their risk of viral infections. “Most normal infections are common in both sexes,” says Altfeld, and people recover from them. Autoimmune diseases, on the other hand, can be serious, and Holmberg worries that estrogen therapy, which reduces testosterone, could increase the risk of developing these diseases.

But the study did not directly examine estrogen treatment or safety. Klein believes it is still too early to say whether the connection between autoimmune diseases and GAHT should be considered. “These are small sample sizes,” she says – 23 people isn’t a lot. “This suggests the need for further research.”

Some doctors are already warning their patients about the connection. Altfeld, who studies GAHT's effects on the immune system, says he works with doctors who inform trans women that estrogen treatment is associated with a risk of developing an autoimmune disease. The potential downside is “known in the community,” he says.

But not everyone has such well-informed doctors. It's "really difficult" to find a medical provider who specializes in multiple disciplines such as immunology and gender-affirming care and can address "intersectional needs," says Jamie, a transmasculine person (assigned female at birth but identifying with masculinity) who suffers from an autoimmune disorder called Sjögren's syndrome and who asked to be under one To be identified using a pseudonym because not everyone in their lives knows about their gender identity.

Jamie chose testosterone therapy for both gender confirmation and to treat Sjögren's syndrome - an action she took based on her own study of the scientific literature, rather than on the advice of a doctor. Since then, Jamie has swapped testosterone therapy for an immunosuppressant called Adalimumab (sold as Humira) to improve her health. Adalimumab inhibits TNF, which is elevated in people with Sjögren's syndrome. Holmberg and Brodin's work has Jamie wondering whether returning to testosterone therapy would reduce the effectiveness of the adalimumab she is taking because her TNF levels could rise. “God, I wish there were studies on this so we knew how the interactions work instead of just guessing,” she says.

Suche

Suche

Mein Konto

Mein Konto