Two studies of more than 100,000 women have uncovered a set of genes that help regulate, when a person enters menopause and thus the length of their reproductive lifespan 1, 2. Some of the genes could also influence cancer risk.

The age of onset of menopause can vary greatly and is influenced by both environmental and genetic factors. The hope is that these genetic catalogs will help researchers Infertility treatments to develop and methods for Prediction of menopause onset age to accomplish. The studies were conducted on September 11thNature 1and on August 27th inNature Geneticspublished 2.

Rare but effective

These studies join a number of current efforts to identify genes that contribute to early menopause. While most of these studies looked for genetic variants that are common in the population, the new projects focused on rare DNA sequences whose effect on ovarian aging may be stronger than more common sequences.

“They are rare but typically have a large effect,” says Anne Goriely, a geneticist at the University of Oxford, UK, who is not one of the authors of the studies. “New treatments and conceptual advances often come from such rare diseases.”

Finding rare genetic variants requires data from a large group of people. To obtain such data, geneticist Anna Murray from the University of Exeter Medical School, UK, a co-author of theNaturestudy, and her colleagues on the UK Biobank, a comprehensive collection of biomedical data, which contains DNA sequence data as well as information about participants' lifestyles and health. The researchers focused on protein-coding DNA and discovered nine genetic variants linked to age at menopause. Five of these genes had not previously been associated with ovarian aging.

Women with certain variants of a gene calledZNF518Afor example, menstruation began later and menopause occurred earlier than women who did not have this form of the gene. The result was a reproductive lifespan that was, on average, more than six years shorter.

Mutations and menopause

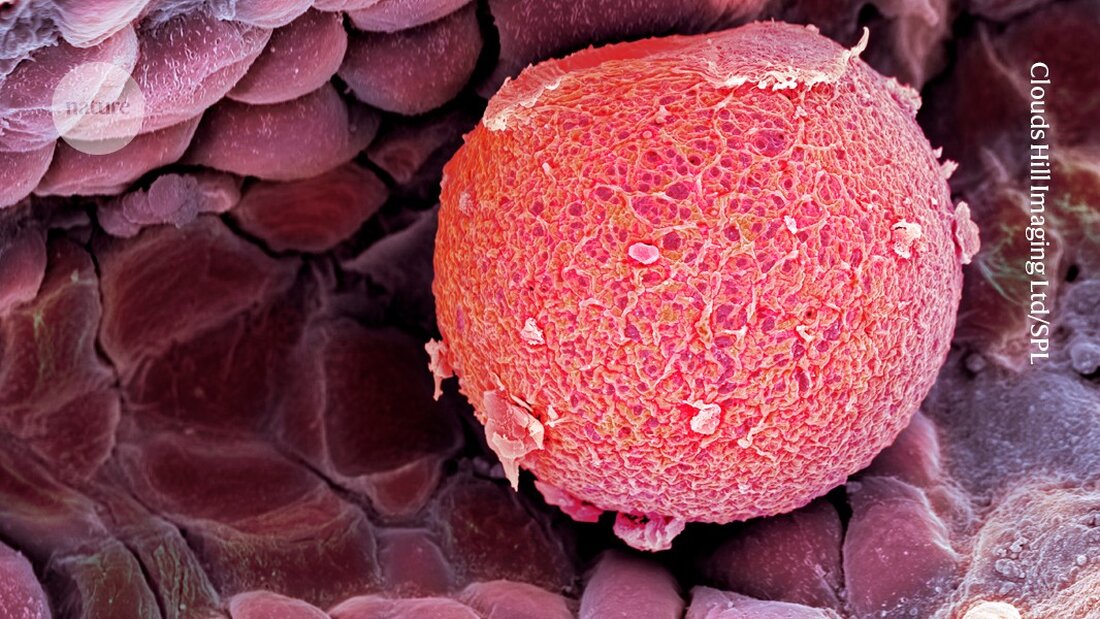

One factor that could trigger early menopause is the accumulation of DNA mutations in a person's ovaries. Such mutations can trigger repair of the eggs' DNA or cause the eggs to self-destruct. Egg response to DNA damage is critical in determining egg number, says Murray. “And egg number determines your reproductive lifespan.”

Mutations can also increase the risk of cancer, and variants in four of the genes the team discovered were linked not only to early menopause but also to a higher risk of cancer.

To investigate the relationship between the accumulation of DNA mutations and ovarian aging, Murray and her colleagues analyzed the genetic sequences of more than 8,000 genetic "Tris" - that of a mother, father and child pair.

The team found that women who carried common DNA variants associated with earlier menopause onset age in previous research were more likely to pass on mutations that arose in their eggs to their offspring.

The results support the idea that DNA damage is linked to ovarian aging, says Murray. However, when the team tried to repeat their experiment with data from a different biobank, the results were no longer statistically significant.

Still, it is important to further explore the possible links between age of onset of menopause and cancer, says Kári Stefánsson, a geneticist and CEO of the biopharmaceutical company deCODE Genetics in Reykjavik and co-author of theNature-Study. “It draws attention to finding a way to deal with conditions like early menopause and the impact it has on biology,” he says.

Infertility treatment

In theNature Geneticsstudy, Stefánsson and his colleagues looked for genetic variants associated with early menopause, focusing on variants that only had an impact if they were present in both copies of a woman's DNA. Their search revealed a link between the age of onset of menopause and a gene calledCCDC201, which is known to be active only in immature eggs 2.

Women with certain variants of this gene entered menopause nine years earlier on average. The great impact and specificity of the activity ofCCDC201suggest that this gene may prove to be a useful target for preventing or treating some cases of infertility could prove, says Goriely. Such an intervention would have to be carefully designed to avoid the risk of passing on damaged DNA to the offspring, but in principle eggs contribute significantly fewer mutations than sperm anyway, she notes.

“You don't die from infertility, but for many women who suffer from it, it really is a catastrophe,” says Goriely. “We should do something for these women.”

Suche

Suche

Mein Konto

Mein Konto