A Range of medications that cause impressive weight loss, has revolutionized the treatment of obesity – and given consumers an unprecedented choice of weight-loss therapies. Now research is beginning to reveal how these drugs might differ from each other, although they work in similar ways.

Semaglutide, tirzepatide and other recently developed drugs for the treatment of obesity and metabolic disorders work in part by mimicking a natural hormone called glucagon-like peptide-1 (GLP-1). However, studies have shown that the drugs differ in their ability to Prevent diseases such as type 2 diabetes 1differ and that some result in greater weight loss than others 2. There are also differences between these drugs and an older generation of GLP-1 drugs, with research suggesting that some of the earlier drugs are more effective against neurodegenerative diseases such as Parkinson's disease 3than later medications could be.

Understanding the differences could help doctors better tailor treatments, says Beverly Tchang, an endocrinologist at Weill Cornell Medicine in New York City. “For example, if someone with obesity has heart disease, I tend to reach for semaglutide first, rather than tirzepatide, because we have the data,” she says, citing a study 4, which showed that Semaglutide reduces the risk of serious cardiovascular events in people with these diseases. But the choice might be different for someone with sleep apnea, she says, citing a study 5, in which tirzepatide reduced symptoms of sleep apnea in people with obesity.

Comparison

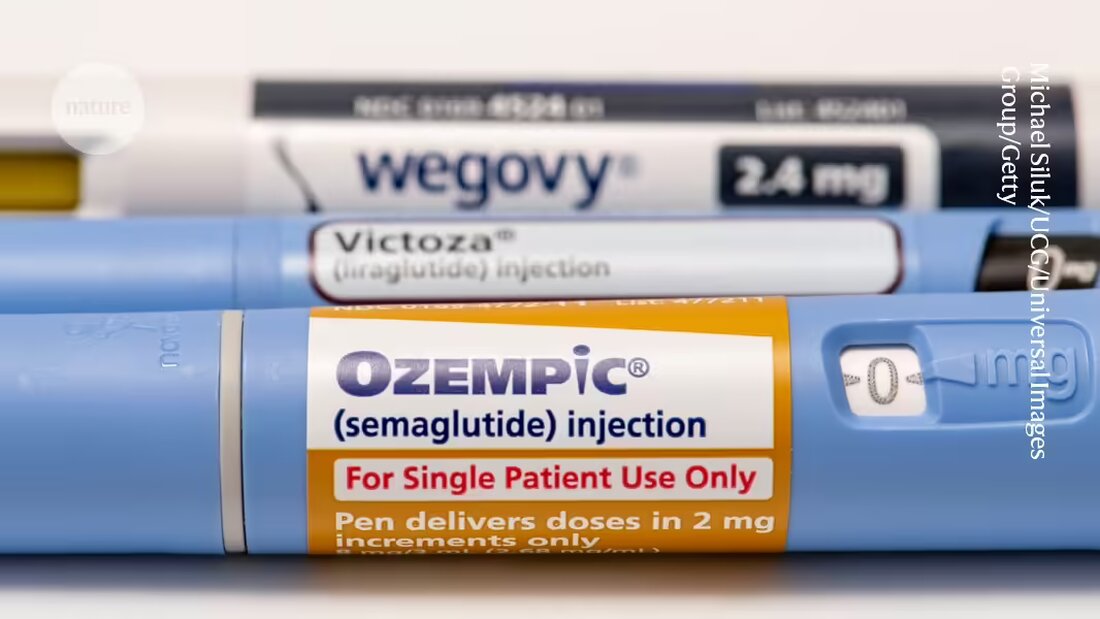

The best-selling weight-loss medications include semaglutide, sold as Ozempic and Wegovy, and tirzpeatide, sold as Mounjaro and Zepbound. A study published this month 1found that tirzepatide is better than semaglutide at preventing the development of type 2 diabetes in people with obesity. Another analysis 2concluded that tirzepatide was associated with greater weight loss than semaglutide in people with overweight and obesity. Researchers are now eagerly awaiting the results of one randomized controlled trial comparing semaglutide with tirzepatide on weight loss and will provide a more definitive answer than previous retrospective studies.

Both semaglutide and tirzepatide mimic GLP-1, which is involved in regulating blood sugar levels and suppressing appetite. This mimicry allows the drugs to activate receptors that are normally activated by GLP-1.

Tirzepatide also mimics another hormone called gastroinhibitory peptide (GIP), which plays a role in fat metabolism. Tirzepatide thereby activates receptors that are normally activated by both GLP-1 and GIP.

However, it would be a simplification to assume that tirzepatide's supposed higher potency is because it targets two hormones instead of one, says Tchang. Tirzepatide “does not activate the GLP-1 and GIP receptors equally,” she says. Instead, the drug binds more effectively to the GIP receptor than to the GLP-1 receptor. One hypothesis is that tirzepatide's GIP activity enhances GLP-1-induced weight loss, although its GLP-1 receptor activation is weaker.

An experimental drug developed by biotechnology company Amgen, based in Thousand Oaks, California, also targets receptors for both GLP-1 and GIP. However, unlike tirzepatide, this drug does not block the receptors. The drug achieved promising weight loss results in an early clinical trial 6.

Scientists are now trying to explain why significant weight loss is achieved both by activating the GIP and GLP-1 receptors and by activating the GLP-1 receptors and blocking the GIP receptors. "There are theories and people are working on them, but I think we should be a little humble and admit that there are still things we don't fully understand," says Daniel Drucker, an endocrinologist at the University of Toronto in Canada.

Saving the brain

GLP-1 drugs not only cause weight loss but also reduce inflammation, which may partially explain why they have potential to help slow neurodegenerative diseases. Both Parkinson's and Alzheimer's diseases involve brain inflammation.

In a small clinical trial, the GLP-1 drug exenatide improved symptoms in people with moderate Parkinson's disease 3. Exenatide was the first GLP-1 drug on the market and received US Food and Drug Administration approval in 2005. A small study of a GLP-1 drug called Liraglutide slowed cognitive decline by up to 18% in people with mild Alzheimer's disease over the course of a year.

Some researchers believe that the better a GLP-1 drug penetrates the brain, the better it could treat neurodegenerative diseases. However, it is not yet clear how far these drugs reach the brain, but animal experiments do 7suggest differences between the GLP-1 drugs in this regard.

For example, exenatide appears to cross the blood-brain barrier, a protective shield that controls which substances can pass from the bloodstream to the brain. Christian Hölscher, a neurologist at the Henan Academy of Innovations in Medical Science in Zhengzhou, China, attributes the drug's initial success in treating Parkinson's disease to this ability.

He notes that a version of exenatide that was modified to remain in the blood longer did not have the same success in treating Parkinson's disease as the original version 8. The modified version is a much larger molecule that cannot enter the brain. “This really shows how important it is to get the drug to the areas where the damage is if you want to improve and protect the neurons,” he says. He also notes that studies indicate that semaglutide cannot cross the blood-brain barrier. “Therefore, the newest medications available on the market for diabetes are very unlikely to have very good effects on Alzheimer’s or Parkinson’s disease.”

But other researchers do not share this opinion. “I don't think we have very good data establishing a correlation between brain penetration and activity in neurodegenerative diseases,” says Drucker.

Suche

Suche

Mein Konto

Mein Konto