Debate over the Alzheimer's drug lecanemab - one of the first drugs to slow cognitive decline in people - is intensifying among researchers and clinicians over whether the treatment's potential benefits outweigh its risks.

On August 22, Britain's Medicines and Healthcare products Regulatory Agency gave the drug the green light. At the same time, however, Britain's health regulator NICE, which determines whether drugs are offered to patients on Britain's state-funded National Health Service (NHS), said in a draft that lecanemab would not be made available on the NHS because the benefits were too small to justify the high cost.

“The unusually long time they spent reviewing the drug suggests that this was not an easy or simple decision,” psychiatrist Robert Howard of University College London said in a statement to the Science Media Center in Britain.

US regulators were the first to approve the drug in 2023, and the European Medicines Agency (EMA) is now reviewing its decision following an appeal by the drugmaker.

Amyloid target

The EMA's decision also received mixed reactions from the Alzheimer's community. “Emotions are really running high here,” says biochemist Christian Haass of Ludwig Maximilians University in Munich, Germany, who disagrees with the decision. “It’s the first disease-modifying drug we’ve had in more than 30 years.” Denying patients access to lecanemab means many lose the opportunity to gain valuable time, according to Haass.

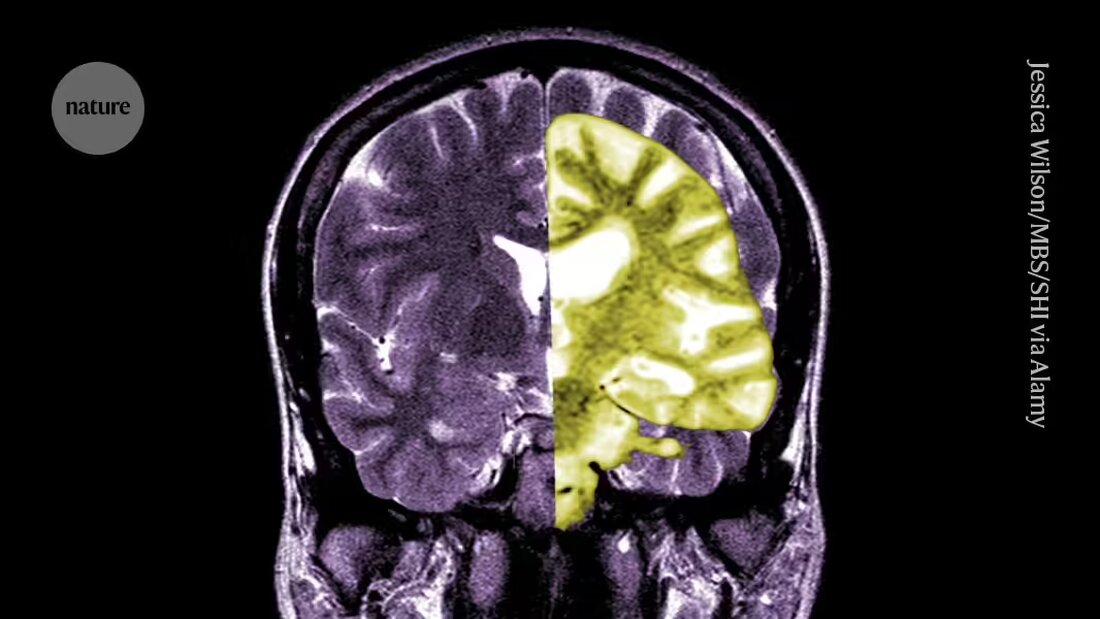

Lecanemab, or Leqembi, is a monoclonal antibody that eliminates amyloid, a substance that builds up into toxic clumps in the brains of people with Alzheimer's. The drug, made by Eisai in Tokyo and Biogen in Cambridge, Massachusetts, is also approved in China, Japan, South Korea and the United Arab Emirates.

Others applaud the EMA, saying that while the drug has been effective in reducing amyloid levels in the brain, whether the resulting reduction in cognitive decline will result in clinically relevant benefits for patients remains unclear. They state that the possibility of serious complications such as bleeding or swelling in the brain caused by a side effect called amyloid-related imaging effects (ARIA), although small, is a major concern. “A reasonable assessment of the risks versus benefits of this drug should lead people to be very skeptical,” says Matthew Schrag, a neurologist at Vanderbilt University in Nashville, Tennessee.

Modest effects

Whether lecanemab administered by infusion provides people with clinically meaningful reductions in cognitive decline has long been debated.

A Phase III clinical trial of the drug, published in 2022, included 1,795 people in the early stages of Alzheimer's disease and found that those who received the drug showed a 27% reduction in cognitive decline after 18 months compared to those who received a placebo. Some researchers celebrated the news as a victory for the field. However, others argued that the effects are too small to have a meaningful impact on patients.

One of the reasons for this difference in perspective is how people look at the data, says Sebastian Walsh, a public health researcher at the University of Cambridge, UK. The 27% reduction represents the relative difference in the amount of cognitive decline experienced by the drug group compared to the placebo group. However, the absolute difference in cognitive function is much smaller: 0.45 points on an 18-point scale. “People can extract whatever they want from the effect size,” says Walsh. “If they want to sell the drug, they could focus on relative changes – and if they are very skeptical, they could talk about the absolute differences.”

But even small effects can become significant over time, particularly in the later stages of the disease when degradation occurs more quickly, says Walsh. “Ultimately it depends on what you think what the long-term impact will be, and we don’t have an answer to that.”

Some long-term data is now available. At the Alzheimer Association International Conference (AAIC) in Philadelphia last month, Eisai and Biogen presented results from an open-label extension study that continued to monitor patients who received lecanemab after completion of the Phase III trial. After three years of continuous treatment, more than half of the patients showed improvement, and most cases of ARIA occurred in the first six months of treatment. They also reported that the rate of cognitive decline returned to placebo levels when people stopped taking the drug, even if the amyloid plaques had been removed before treatment was stopped.

Some are optimistic about these results - Haass says it's exciting to see that the drug not only eliminates amyloid, but also slows the spread of tau, another protein that builds up into clumps in the brains of people with Alzheimer's. Others are more cautious. Paresh Malhotra, a neurologist at Imperial College London, points out that the positive results presented at AAIC were not compared to a placebo, so more data is needed to determine the drug's long-term effectiveness.

Cost is also a concern. Walsh says that given the drug's modest effects, it is difficult to justify the cost of administering the drug (which costs more than $20,000 a year in the U.S.) and the procedures required, such as imaging and genetic testing, to identify eligible people to receive it.

Safety concerns

The biggest concern with lecanemab is ARIA, which the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) warned about in its approval. Although most cases are asymptomatic - and none were reported during the initial 18-month clinical trial - there were some ARIA-related deaths in the extended phase of the study.

Some experts say that although the risk of severe ARIA is low, it is also important to consider that the drug is given in the earliest stages of Alzheimer's. “This is the period in which people have the most to lose,” says Schrag. “During this window, we often encourage patients to travel, think about their bucket list, and accomplish the things they want to accomplish in life.”

Ellis van Etten, a neurologist at Leiden University Medical Center in the Netherlands, says there are still many unanswered questions about ARIA and how doctors should respond when they see patients developing these abnormalities during treatment. For example: Who will develop serious or life-threatening ARIA? At what point does ARIA go from harmless to harmful and when should lecanemab treatment be stopped?

Many of the same questions about benefits and risks also apply to another amyloid-clearing antibody, donanemab — made by Eli Lilly in Indianapolis, Indiana — which was approved by the FDA in July. Donanemab appears to provide about the same reduction in cognitive decline as lecanamab – and it has been linked to ARIA-related deaths.

“We know from biomarker work that these antibodies clear amyloid, so we know they address a fundamental mechanism of the disease,” says Malhotra. But these medications alone probably won't be enough, and it will be important to address other aspects of the disease as well. “It is very likely that in 10 years we will be talking about combination therapies and that amyloid clearance will be part of that approach.”

Suche

Suche

Mein Konto

Mein Konto