COP29 climate deal: historic breakthrough or disappointment? Scientists' reactions

Researchers assess the new COP29 climate agreement approach in Baku: historic breakthrough or disappointing compromise?

COP29 climate deal: historic breakthrough or disappointment? Scientists' reactions

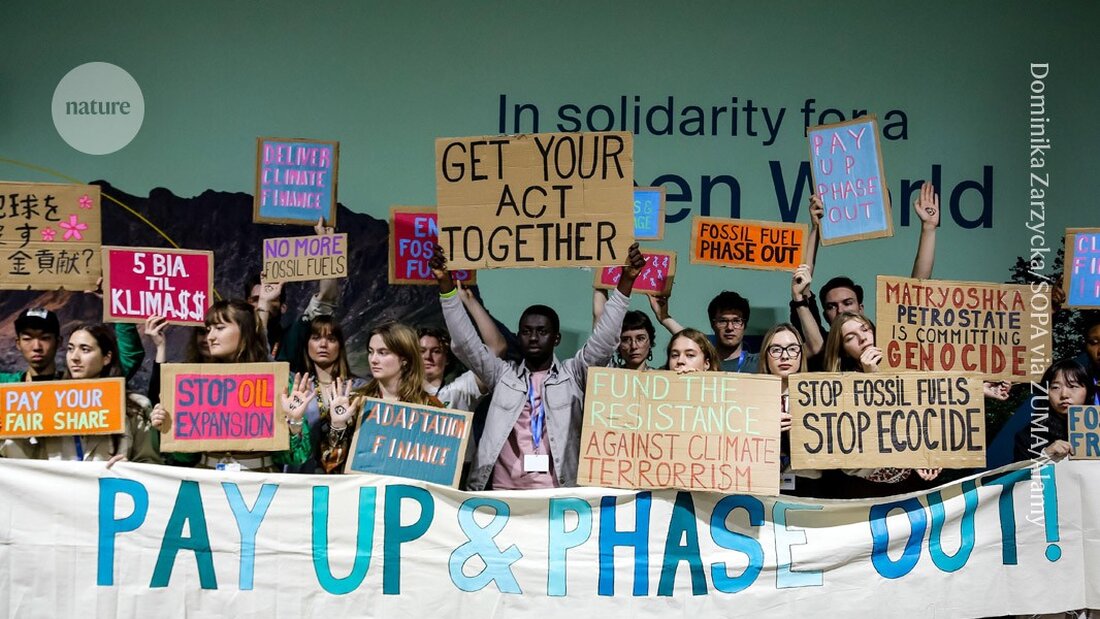

A short-term deal that saved the COP29 climate conferences in Baku, Azerbaijan, is a “fragile consensus,” climate finance researchers have told Nature.

Relieved COP delegates from wealthy countries applauded in the early hours of November 24 after a short-term pledge that wealthy countries will "take the lead" in increasing climate finance for poor countries to at least $300 billion annually by 2035. Low- and middle-left income countries, particularly China, are also expected to contribute to international climate funds, marking a first for a COP agreement.

But delegates from some of the largest developing countries, including India, Indonesia and Nigeria, were angry. Some alleged that they were pressured to reach a deal so that the COP session did not end in fiasco. Additionally, it has not been determined how much of the $300 billion will come in the form of grants or loans, nor how much will come from private or public sources.

Current climate finance from rich to poor countries is over $100 billion and is expected to rise to nearly $200 billion by 2030 under a business-as-usual scenario, one said Analysis by ODI Global, a think tank in London.

The disappointment with the result

“The financial offer for Baku was extremely disappointing,” says Dipak Dasgupta, an economist at The Energy and Resources think tank in New Delhi and lead author of climate finance reports for the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change.

“While there is a brief moment of joy at having pulled this COP from the flames, this meeting also exposed old wounds between wealthy and poor nations,” notes Clare Shakya, climate director at The Nature Conservancy, an international conservation organization based in Arlington, Virginia, USA.

Low- and middle-left income countries, excluding China, approached the COP proposing to wealthy countries that they would need about $2.4 trillion annually by 2030 to divest from fossil fuels and protect themselves from the effects of global warming. This sum corresponds to the recommendations of one influential report, which was presented by scientists and economists. To get closer to a deal during the COP, more than 80 countries proposed a sum of $1.3 trillion.

“The promise of $300 billion a year by 2035 will not convince anyone that we will achieve the $1.3 trillion a year needed to address the climate crisis,” says Sarah Colenbrander, head of climate and sustainability at ODI Global.

The Trump factors

The agreed amount also does not reflect a scenario in which the United States withdraws its global climate financing in the event of an incoming Trump administration withdraws from international climate agreements.

Before the COP, US President Joe Biden's administration was committed to providing $11.4 billion in climate finance annually through 2024, about 10% of the current annual global total. “There is no doubt that we will see an enormous hole in global climate finance provided [by the US] as climate impacts intensify and accumulate,” says Shakya. In contrast, China has provided about $4 billion in climate finance annually since 2013, she adds.

COP delegates also agreed that a financial “roadmap” document will be produced before COP30 in Belém, Brazil, showing how countries will achieve the higher climate finance target.

“The Baku-Belém roadmap is there for a reason, and good practical science is urgently needed,” says Dasgupta. “It needs careful care, not a wrecking ball.”

Suche

Suche

Mein Konto

Mein Konto