Harassed or intimidated? A guide helps scientists in crisis situations

A new guide offers scientists strategies to protect themselves from harassment and intimidation, supported by institutions and organizations.

Harassed or intimidated? A guide helps scientists in crisis situations

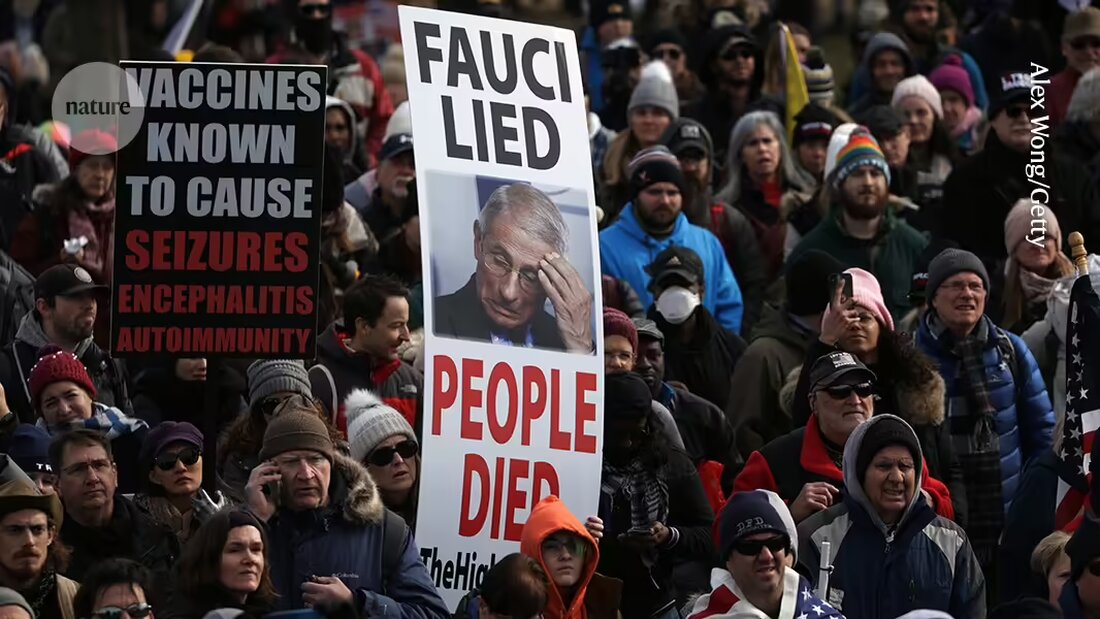

Intimidation and harassment have become an occupational risk for scientists who study political phenomena such as Climate change, disinformation and virology occupy. Now researchers have come together to create a defense handbook that offers tactics for dealing with this reality. Their message is clear: Scientists can take steps to protect themselves, but their institutions must also have a support plan.

“Universities and academic institutions have the primary responsibility to act,” says Rebekah Tromble, who directs the Institute for Data, Democracy and Politics at George Washington University in Washington DC and has experienced harassment herself as a result of her professional work. “They are the employers and, quite frankly, it is the kind of publicly funded research they promote that puts scientists at risk.”

Tromble worked with Kathleen Searles, a political scientist at the University of South Carolina at Columbia, on an initiative called Researcher Support Consortium, which launched today in Washington DC. Supported by several nonprofit organizations, they have developed a series of recommendations for researchers, funding agencies and academic institutions, including template policies for universities that outline best practices for dealing with attacks on their scientists.

The consortium is not the first to tackle this issue, but it has provided the most comprehensive guide available, says Isaac Kamola, a political scientist at Trinity College in Hartford, Connecticut. “It’s the new industry standard,” says Kamola, who is also director of the American Association of University Professors’ Center for the Defense of Academic Freedom, which has one of its own Hotline for researchers affected by harassment.

Consortium advice for researchers who believe they are at risk begins with simple steps, such as removing personal contact information and office addresses from publicly accessible websites. But the organization also points to more sophisticated strategies, such as applying for a “ Certificate of Confidentiality " from the US National Institutes of Health, which protects the privacy of participants in research studies. Funding agencies and project managers are encouraged to send supportive messages to both grantees and their research institutions.

However, the majority of the consortium's recommendations focus on academic institutions. Her 43-page toolkit outlines steps universities can take to prepare for attacks on their academics, rather than looking for blank bullets to respond to harassment after it has already happened. The first steps are to implement policies, establish codes of conduct for students and professors, and create reporting systems. Institutions should also establish committees of administrators, department heads, communications staff, legal counsel, and others willing to act.

Experts contacted by Nature say these are useful guidelines and will help if followed. “Unfortunately, I don’t think it will stop researchers from needing their own lawyers when things get serious,” says Lauren Kurtz, executive director of the Climate Science Legal Defense Fund, a New York City nonprofit founded in 2011 to provide free legal help to climate scientists. The fundamental problem, Kurtz said, is that institutions are often more focused on protecting themselves than supporting their employees, and often decline to provide legal assistance to their employees.

The Association of American Universities in Washington DC, which includes more than 65 US public and private institutions, did not respond to Nature's request for comment.

Tromble says the consortium is designed to work in parallel with organizations that provide legal support to scientists. The latest to launch such a service is the Knight First Amendment Institute at Columbia University in New York City, in November last year announced, that it would offer legal support to researchers studying social media.

The stakes are high – for researchers, for science and for the country, says Kamola. “Defending faculty against harassment is critical to protecting the long-term integrity of research, the integrity of the institutions in which we work, and the integrity of our democracy.”

Suche

Suche

Mein Konto

Mein Konto